August, 2022

Time is not what we think it is. What we perceive it to be. Time seems to pass steadily, in just one direction. We regulate our lives with time; our perceptions are full of what seem to be regular, reliable cycles and markers. The sun rises and sets. Our hearts beat. Living creatures, ourselves included, are born, grow older, and eventually die.

There are hints, here and there, that things are not quite so simple. The older you get, the faster time seems to pass. When you’re five, waiting for your sixth birthday seems to take forever, but when you’re fifty-nine, the wait for your sixtieth doesn’t feel very long at all. And while we only remember things in the past, not the future, most people have experienced a few episodes of deja vu, which almost feels like you’re remembering something from the future.

The way we communicate now, by phone and text and email, is all perceptually instantaneous. That makes it seem like time is pretty universal — although your friend halfway across the world sees the sun or moon at a different spot in the sky, it’s still “now” at the same time for both of you. Or so it feels. Traveling is fast now too. When you end a journey thousands of miles away on the same day you started, it’s easy to visualize both locations; the trip’s start and its end, at the same moment.

The same kind of “stuff” — technology — that we rely on to reinforce our implicit sense of time is what enables us to know for a fact that our experience of time is not the whole story. Travel fast enough and time slows down for you, relative to somebody traveling more slowly. Einstein predicted this, and experiments have demonstrated that it really works that way. Even a trip in an airplane affects the time you experience. You just need a very, very precise instrument to measure it (or, really, two instruments; one on the plane and one not).

I wonder if the human sense of time was different back in the days when a long trip lasted months or years, simply because ships, horses, and feet were slow. Did it seem like the now you experienced after weeks at sea was the same moment your friends at home lived in?

John Donne, the English poet, wrote A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning in 1611 (or so) and talked about a connection between two widely-separated lovers being like the two legs of a compass (the kind you use to draw a circle, not the north-pointing kind). That image carries a powerful sense of sameness or connection across space and time. When you move a compass, the whole thing moves as one; you don’t think of the two legs being in different moments of time.

Maybe they are, though. Picture the same compass, the same conceit discussing a distant connection — but now the connection is between you as you are today and your younger self. That’s one of the ways we perceive time — there’s not really that much similarity between a person at ten years old and “the same” person at fifty, but that fifty-year-old remembers being ten. There’s an internal continuity between your former selves and the current you. That helps convince us of our perception that time is something like the flow of water.

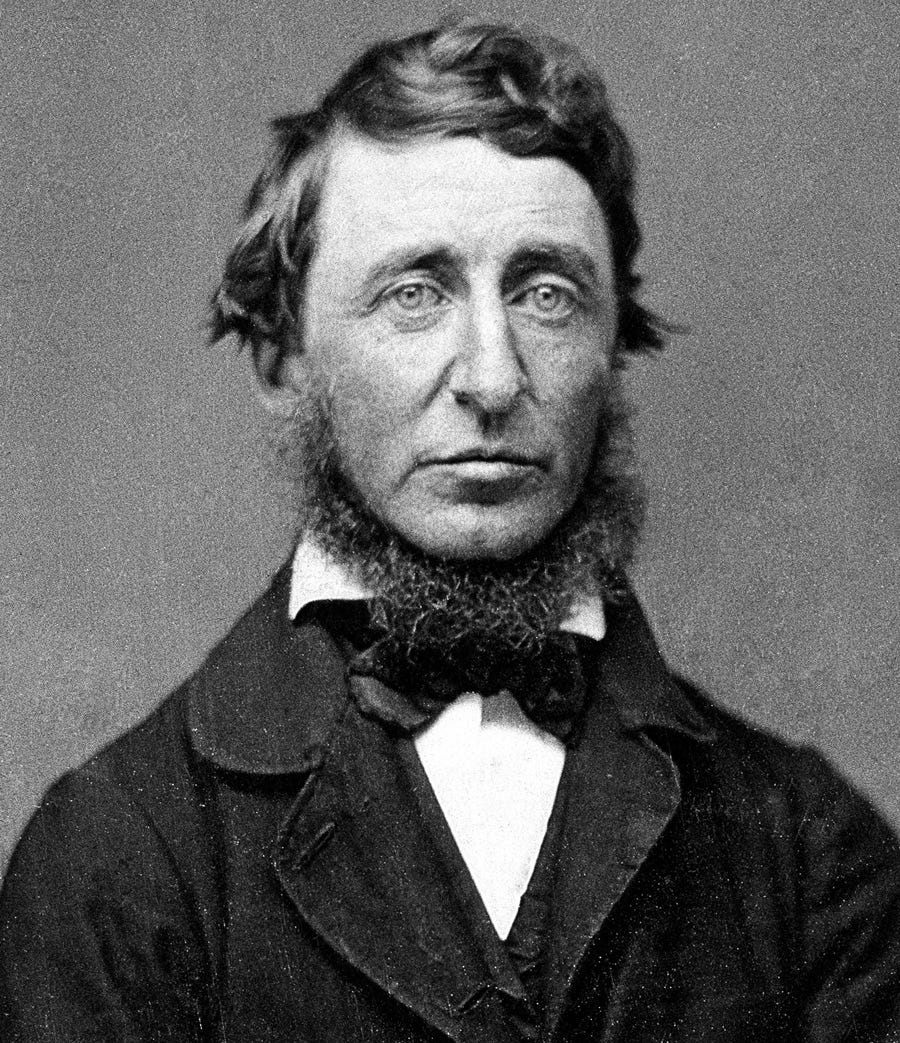

Henry David Thoreau, the American transcendentalist writer, included in his book Walden this passage: Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in. I drink at it; but while I drink I see the sandy bottom and detect how shallow it is. Its thin current slides away, but eternity remains.” He’s talking about time as flowing water, but also as something else — the “sandy bottom.” A solid surface.

What if time is a kind of solid? A solid that lies outside our experience and is both fixed and maybe in some kind of motion as well. Everything that, to us, has happened and is yet to happen would all exist in this one state. Alan Moore creates a place like that in his novel Jerusalem (which does not take place in Jerusalem). It’s called “upstairs” and Michael Warren arrives there when, at age 3 or so, he chokes on a throat drop and dies. It’s vast — maybe infinite — but he can look down into what he perceives as rooms. “Those frilly dragon statues down there in the instant’s diamond varnish were his mum and gran and sister.” Minor spoiler: the whole episode turns out to something of a cosmic mistake, and Michael is sent back downstairs, but he — and the readers — are left with the memory of the place and the experience.

Memory is probably the key to our perception of time. I can remember yesterday, and five minutes ago, and years ago. At least I think I can. Because I’ve internalized the idea of “computers,” the great metaphor of our age, my default idea of memory is a separate part of my mind where “stuff is stored.” But I wonder if that’s a useful way to think about it. Sometimes I think that memory is just part of my condition in life at any given time — that is, the things I “remember,” however that works or doesn’t, are just part of the totality. If I remembered something different, I’d be a different person, not the same person that remembers something else.

Stuff happens. That seems pretty certain. A thing that happens changes something else, and sometimes that something else is me.