Some of the features of the infrastructure of the modern world include bridges with very wide spans, tunnels under rivers, standardized railroads, ships driven by propellers, ships that are really big and made of steel…I could go on. An amazing number of these were first designed and built by one man: Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who was born April 9, 1806 in England.

Brunel was a pretty smart boy; he learned geometry by eight years old, and by then could also speak fluent French as well as English. He also liked to draw, and would sketch buildings and point out problems with their design. His father, who was a civil engineer, could see that his son would benefit from a high-quality education, and sent him to a boarding school in France (where the best schools were thought to be at the time). Brunel did pretty well there too, speeding through his classes and enrolling in the University of Caen when he was just 14.

Brunel graduated from university when he was 18, and became an apprentice to a famous clockmaker. Apprenticeships usually last years, but the clockmaker declared Brunel’s to be finished later the same year, as there was nothing about clockmaking he hadn’t already learned. So Brunel traveled back home to England. He became an assistant engineer on a project headed by his father to tunnel under the Thames river. It was a troubled project, and Brunel himself was injured pretty seriously in an accident. It took him six months to recover. To keep busy, he designed a suspension bridge to be built out of wrought iron. It’s still standing and even today is pretty impressive: the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, England. It was the longest bridge in the world at the time.

Brunel went on to design dozens of bridges in England — many for the Great Western Railway, for which he was the chief engineer. He also designed the Great Western steamship to fulfill his idea of people being able to buy a single ticket in London and travel all the way to New York City. As chief engineer of the railway, he had a hand in designing practically everything connected with it, from the width of the tracks to the stations (including London’s Paddington Station, which still exists as he designed it) to some of the hotels across the streets from the stations.

One of Brunel’s lesser-known (and less successful) projects was the “atmospheric railway.” This was a train without locomotives. Instead, there was a pipe in the center of the tracks, and a series of pumps sucked the air out. The vacuum was used to propel the trains. It actually worked, and 68 miles of track were constructed between Exeter and Newton, with pumping stations every two miles. The trains ran at the then-astonishing speed of over 100 km/hr. The system had one big flaw, though. The vacuum pipes had to transfer the vacuum to the trains somehow, and the technology of the time offered only one option: leather. In order to make sure the leather didn’t dry out (and leak all the air), it had to be maintained with tallow. And rats love tallow. The railroad operated for nearly a year, but the difficulty of maintenance in the face of hungry (and appreciative) rats proved to be too much.

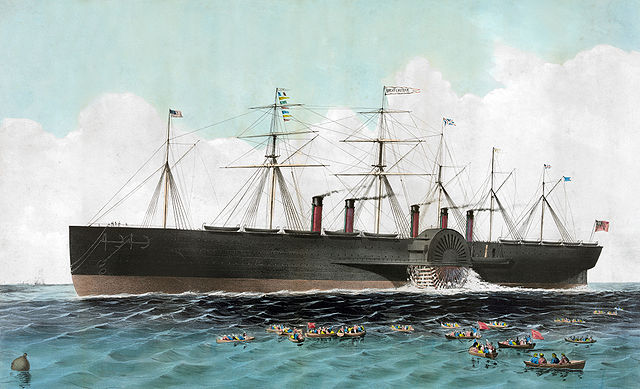

In Brunel’s time the idea that a ship could be propelled by steam engines across an entire ocean was by no means settled. Steam engines of the day were pretty inefficient, and it wasn’t clear that a ship could carry enough fuel and fresh water for a ship to travel that far. Brunel calculated that the larger a ship is, the more efficiently it can move through the water, and so would require proportionately less fuel. So he designed his first ship, the Great Western. It was the longest ship in the world in its day. This one was built of iron-reinforced wood (Brunel’s later ships were all iron), and proved that a steamship could have sufficient range to cross oceans. Brunel’s next ship, the Great Eastern, was designed to cruise from London to Australia and back without refueling (they hadn’t found any coal in Australia yet), and was the world’s largest ship until the 20th century.

Unfortunately there wasn’t yet much of a market for passenger travel between Europe and North America, and Brunel’s ships were too far ahead of their time to be economically successful. The Great Eastern was converted from a passenger liner to lay the first undersea telegraph cables.

Lots of Brunel’s projects were like that — technically innovative, but too far ahead of their time. Brunel himself was ahead of his time in a less positive way; he was a heavy smoker, and it killed him at 53. There are memorials and remembrances of Brunel throughout England, and many of his bridges, tunnels, and buildings are still there. In 2006 two new two-pound coins were minted to commemorate his 200th anniversary. And in the 2019 novel The Great Eastern, Brunel is one of the main characters.

Illustration is the Great Eastern, by Charles Parsons (1821-1910) – http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b51503, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6693878