“Ronald! Ronald, come here immediately!”

“On my way, Professor,” came the reply from the storeroom. Ronald emerged, carrying a jeroboam of the acetic acid Professor Q had sent him to fetch. He set the large bottle down carefully and rushed to the Professor’s side.

“Look at this, Ronald, just look!” The professor indicated his shoes.

“Wh…what happened, sir?” asked the assistant.

“Well obviously the pannuscorium of my shoes has been utterly ruined by that oil,” fumed Professor Q. “Of all my inventions, the Automaton is the first one I’ve begun to feel is suffused with amarulence toward me. The more I try to bring my vision to reality, the more I attempt to avunculize the Automaton, the more it appears intent upon worsening my bajulation.”

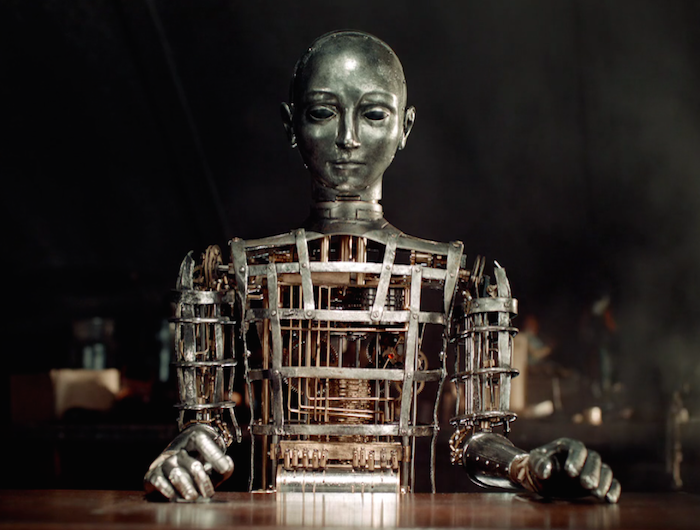

The professor fixed the Automaton with a steely glare. The gleaming metallic face, still somewhat marred by the brochity that had not yet been corrected, regarded him blankly, as always.

“Er, Professor, did you still want this acetic acid?” asked Ronald. In his two years working for Professor Q he had learned that changing an unpleasant subject was often the best course of action.

“Yes, of course, of course,” said the professor. “Pour exactly 1 dram into hose number three, Ronald.

Ronald carefully measured out the acetic acid and poured it into one of the hoses connected to the torso of the Automaton. He had the momentary sense that the Automaton shivered, but shook his head. It must have been a trick of his eyes. Or possibly the passing of the streetcar in the avenue just outside the laboratory.

“Professor?” he said, “why do we only use bitter solutions in the Automaton? Vinegar, acetic acid, lye…don’t we need something to balance the…”

“I hope you were not about to say ‘balance the humors’”, snapped Professor Q. “That would be a commentary worthy of that imbecilic papicolist Witherspoon! He’d doubtless be claiming that administration of a panchymagogue — to an Automaton, mind you — would be a course of action worthy of rational inquiry!”

“Er, no, no, I wasn’t thinking anything like that,” said Ronald, who had, in fact, been thinking something quite similar. “I was just concerned about…corrosion of the seals.”

“Ah, I see,” said the professor, instantly calming from his impending rant against his greatest rival. “A thoughtful consideration, Ronald, and something we should consider. Assemble a test immediately; soak some of the leftover seals in solutions of the various reagents we use and make careful notes about the results over the coming weeks.”

“Yessir,” said Ronald, and he withdrew to the other side of the laboratory to set up the tests on a spare bench.

“Now,” muttered Professor Q to himself, turning back to the blackboard he’d been covering with chalked equations, “how to mediate and detect the emergence of auturgy in chemo-mechanical assemblages…OW!”

He hopped on one foot as he contemplated the large iron bolt that had, somehow, fallen from the bench next to the Automaton directly onto his toe. Which was still, he realized, enclosed in his new shoes, which would now have to be discarded thanks to the oil stains on the pannuscoria. In addition to fancying himself the foremost inventive genius in the world, the Father of Steam Automation, as he was often labeled in the newspapers (thanks to his well-paid press agent), Professor Q took a great interest in his appearance. One could never be sure, after all, when a steam-powered rotofloctuator might appear outside the third-story window carrying a mechanated heliogramaton. Sometimes he almost regretted inventing those.

At the Inventors Club

Professor Q sipped his tea and regarded the various hushed conversations taking place in the Inventors Club library. He turned back to his companion. “No, Edwards, I just can’t contemplate the notion at all,” he said. “Witherspoon is simply a phlyarolgist whose attendance at the Club while I discuss the fabrefaction of my Automaton would be completely unacceptable. I insist that we continue to adhere to our agreement to attend only on alternate days. Should I encounter that pitiful foppotee, I shan’t be responsible for the outcome!”

Edwards sighed. “Professor, I must say I am disappointed,” he said his customary guadiloquent tone. “I am tempted toward ingeniculation, though I fear such a gesture would be in vain.”

“Quite so,” sniffed Professor Q. “Whatever cordiality once may have existed between Witherspoon and myself is irredivivous.”

“Very well,” said Edwards. “It affords me no lubency to do this, but in my capacity as president of the Inventors Club, I have no choice but to inform you, sir, that while Colonel Witherspoon will not be welcomed to the Club in two days on the occasion of your presentation, one of his Inventions will be placed in the hall.”

“This is absurd!” sputtered the professor. “Your message misquemes me to the extreme!” He sighed again, resigning himself to the inevitable. “I do regret that Witherspoon — who, mind you, I regard as a cloakativic aretaloger — is to have even such an indirect presence in my celeberrimous exposition. Nevertheless I shall endeavor to ensure the eveniency of my colloquium.”

“Sir,” said Edwards, who knew enough to accept even a small victory when it was offered, bowed to Professor Q. “I shall convey the news to the Committee.”

Edwards hurried off to find the Committee members. Professor Q harrumphed to himself and chose a volume from the nearest bookshelf. Treatise on the Inventication of the Scandiscope, he read. “Ah, by Humphrey Humphries the Fourth, a towering intellect of his day,” he muttered. “I believe this to be the chap whose sementine researches led to our present-day efficiency in the agricultural arts. I believe there is a solennial celebration devoted to him next to the remaining four acres of farmland needed to feed the nation.” Seeing an approaching clique of colleagues — lesser colleagues, to be sure, but fellow members of the Inventors Club at the least — he replaced the tome and turned to accept what he anticipated would be yet another episode of adulatory congratulations. He found sessions of that sort to be utible in the extreme.

The Inventors’ Assembly

The president of the Inventors’ Club gaveled the meeting to order. It was no small feat to achieve order among the dozens of inventors in attendance, each of whom considered himself independent, cantankerous, and eccentric. Cultivation of irascible eccentricity was nearly a requirement of membership. It often seemed the more creative the inventor, the more outlandish the costume, behavior, or language he affected. Perhaps the worst offender was Professor Q, who today was outfitted in a royal blue one-piece suit festooned with pockets of every shape and size, a wide black leather belt with various metal objects that might be described, loosely, as tools, and a white pith helmet with three sets of goggles, all different, installed above the brim.

The clamor settled down after a few moments, and when the president judged the noise level sufficiently abated he stood, calling out “Hear ye, hear ye! This special session of the Inventors’ Club has come to order at six in the evening on this twenty fifth of July. As this is a special session, we have no Old Business to address. Our New Business is limited to one item; we are here to honor a most illustrious member of our society by bestowing upon him the Phlogistonic Orb of Rigor. The Orb is our society’s highest honor, and represents the pinnacle of inventive creativity, scientific acuity, and naturalistic insight, and ruthless determination.”

He paused for the expected round of applause, which the audience delivered with precision. There were scattered cries of “hear, hear!” And “well said, sir!” The president waved them back into silence.

“As many of you know,” he continued, “our honoree has exhibited a long list of astonishing achievements, to which his latest accomplishment marks an even higher pinnacle of perspicacity than ever before.”

He paused for more applause. He was particularly happy with the phrase “pinnacle of perspicacity,” and had quite forgotten that it had been his wife who had suggested it. “This latest and most audacious achievement, which only some of you have witnessed thus far, will be demonstrated to our society as part of this award ceremony.”

The applause to this was more enthusiastic. As club members, the inventors of course appreciated a good bit of oratory, but even better was the public unveiling of a new invention. And if the rumors were true, this one was going to be spectacular.

“And so, esteemed members of the Inventors’ Club, without further temporal fusitvation, I give you the recipient of the Phlogistonic Orb of Rigor, Professor Q!”

The applause following the culmination of the president’s introduction was somewhat less enthusiastic than he had hoped. It was perhaps due to the professional jealousies that seemed to be unfortunately unavoidable in such a gathering. It might have been due to lingering confusion over his mention of ‘temporal fustivation’, which was an expression the president himself had coined, but which, to his chagrin, had not yet achieved currency. It might even have been due to a certain reluctance among the more tradition-minded members to celebrate a member who had always cloaked himself in a certain amount of enigma, even to the extent that not one of them knew the professor’s real name, nor the source of the honorific “professor” — it was simply the only way anyone had ever heard him addressed.

Nevertheless, applause was applause, and Professor Q beamed as he stepped to the podium. He raised his palms in the customary gesture to quiet a boisterous crowd. The gesture was almost certainly redundant in this circumstance, but he nevertheless enjoyed it.

“Friends and colleagues,” began the professor, ignoring the fact that he considered few of them friends and fewer true colleagues. “I thank you for this honor, which I accept in grateful humility.” He turned to the president, who had brought the Orb to the podium for the formal presentation. The Phlogistonic Orb of Rigor was a crystal sphere mounted on a cubical base of what appeared to be polished brass. True to its name, the Phlogistonic Orb glowed as if a fire had been kindled within it, although the surface was perfectly cool and the steady glow never dimmed. Although any of the members would have happily admitted to its invention, in fact the Orb had simply been discovered in a distant ruin by a member of their sister organization the Adventurers Club. There had been nearly a dozen identical artifacts in the uncovered trove, and the discoverer had distributed several of them as commemorative trophies to clubs and organizations with which he was associated. “Phlogistonic Orb” was simply the name the Inventors’ Club had bestowed on the object; the Adventurers Club called theirs the Globe of Discovery, and the version bestowed by the Philosophers Society was simply Agnes.

Professor Q looked deeply into the Orb, as if trying to puzzle out its secrets — which was exactly what he planned to do once he had it safely stashed in his laboratory. “I will keep my remarks short,” he told the crowd, which was authentically appreciative of that, at least. “And let my work speak for me, as it always does. However,” he added archly, “in this case, that is even more true. Gentlemen, allow me to introduce my greatest work: Elektra!”

Professor Q made a grand gesture to the side, where some curtains blocked the corner beside the podium. There was a collective gasp as Elektra itself — or possibly herself — strode smoothly from behind the curtain and stepped to the podium. Elektra was approximately humanoid, and walked normally, if a bit stiffly. There was no obvious hint to the motive power of what was clearly a self-propelled automaton; its metal surface gleamed in the gas lights, and its eyes flashed — either reflecting the light with unusual efficiency, or perhaps lit somehow from within. Professor Q’s assistant, Ronald, waited behind the curtain and watched nervously. He wasn’t at all sure the automaton was ready for exhibition yet, particularly to such a potentially critical audience.

Elektra placed gleaming metal hands on the sides of the podium, head rotating slightly from side to side as if the automaton was scanning the crowd in recognition. There was an undercurrent of murmuring from the gathered inventors as they muttered astonished comments and skeptical questions to their neighbors, but as the automaton raised hands in an eerie duplicate of the gesture Professor Q had made moments earlier, the crowd fell completely silent.

The sound that emanated from the automaton — its voice — raised the hairs on the necks of all present. It was a manufactured voice, of course, not entirely monotone, but nearly so. A mechanical hum could be detected beneath it. “Greetings all,” said Elektra, “my name is Elektra. I am prepared to entertain questions at this time.”

Behind the curtain, Ronald frowned. That hadn’t been one of the possible opening lines he had programmed in. The professor must have added that one.

One of the inventors in the crowd called out “What is your motive power?”

“I am fueled by ectonic waves,” answered Elektra smoothly. “Ectonic waves are a discovery of my inventor, Professor Q. They are an inexhaustible power source, and cannot be blocked or hindered by walls of any construction, including solid iron.”

“What are your capabilities,” came the next question.

“I am able to speak, as you are now aware,” said Elektra. “I am also capable of locomotion, both horizontally and demivertically. I can climb staircases and ladders. I can grasp and lift objects within limits of size and weight. I am able to read and write in any language and alphabet represented in the professor’s impressive library. I hope to augment my language skills by visiting the library of Byronton University soon. And I am adept at mathematical calculations.”

“But can it see?” came a shouted query.

“My visual acuity is considerable,” came Elektra’s eerie tones. “My ocular sensors detect the same spectra your own eyes sense, and much beyond that. In the breast pocket of your suit, sir, I am able to see a folded sheet of paper concealed in an envelope. I am able to read the words on that paper, which informs you, sir, that your laundry awaits you at your convenience at an establishment called Clean Hilda’s.

At the calls from the audience from “can that be so” to “show the envelope, sir”, the questioner drew the envelope from his pocket, extracted the note from his launderer, and held it up for inspection. Gasps were heard. “A possible confederate!” rang out one voice from the rear. “Tell me, Elektra, can your ocular sensors pierce this mask?” A tall inventor in the very last row stood, holding up a packet the size of a sheet of writing paper. The packet was enclosed in ordinary yellow shipping paper, and could be seen to be unusually thick.

Elektra’s head moved, focusing on the packet. “My visual acuity is considerable,” the automaton repeated, “in spite of the sheets of lead in that packet, the enclosed paper is visible to me. It is an article from the Byronton Times of this morning in which you yourself are quoted, Doctor Witherspoon.”

The tall inventor jerked, startled to be unmasked. Professor Q, still standing proudly beside Elektra, roared in outrage. “Witherspoon! Here?” He spun, confronting the club president. “Edwards! I thought we were in agreement…”

President Edwards, as he customarily did, wilted before Professor Q’s verbal onslaught. “I…I did not expect Doctor Witherspoon to flaunt our agreement,” he protested weakly, “even though there was a certain informality to it…”

“Poppycock and balderdash!” shouted the professor. He spun away from Edwards, sputtering dismissively. “Witherspoon, you imposter! What is the meaning of this?” he yelled.

The tall inventor removed the ascot that had been partially obscuring his face. It was Witherspoon for certain. Reginald Tompkins, a nondescript inventor who had also been seated in the last row, turned to Witherspoon in confusion. “But Doctor,” he ventured, “have you by chance invented a growth serum? When last we met — I believe that was last evening — your height was…that is, you were…”

“Yes, yes, I was as vertically abbreviated as you,” snarled Witherspoon. “I am no taller, sir; I am simply in disguise. To no effect, it seems.” Witherspoon sat down and pulled up the legs of his trousers, revealing stilt-like devices affixed to his ankles. He unstrapped and discarded the stilts and arose, rising to his normal height. He was, as he had admitted, rather abbreviated in that dimension. He turned his attention to the front of the chamber where Professor Q was still glaring at him.

“Professor,” said Witherspoon, “I am here out of an obligation that transcends any mere procedural nicety adopted by a topical society such as ours. My obligation, sir, is to the truth, and I am here to further the interest of truth as regards this latest escapade of yours.”

“Escapade?!” roared the professor. “To what, sir, do you refer?”

The audience, which had been thrown into noisy tumult by the surprise appearance and unmasking of Witherspoon, quieted down in anticipation of an even better show than they had anticipated.

“I refer,” said Witherspoon, “to the fraud you are perpetrating even today, sir!”

Ronald, still behind the curtain to the side of the podium, gulped. Professor Q was turning purple and beginning to tremble in rage.

“That…that thing you claim to be an automaton,” continued Witherspoon, “it is nothing but a costume, sir, very much the same as the deceptive garb I was forced to don in order to gain entrance to this farce!”

When Witherspoon referred to Elektra, many inventors in the audience turned to look beside the podium where the gleaming figure had been standing quietly. There was a murmur of concern as they realized the automaton was no longer there. Ronald froze as he, too, realized Elektra was gone. He heard the inventors asking each other “where did it go? where is it?” and craned his head as far as he could, scanning the hall. Then he saw her, gliding smoothly through the shadows on the darkest side of the hall, approaching the last row of seats.

Ronald considered for a split second — the professor had given him strict orders to remain unseen behind the curtain, explaining that of all the laboratory assistants employed by all the inventors, he was the only one allowed to attend at all, and he should consider himself lucky. But this situation was clearly unexpected, and called for action. Ronald started running toward Elektra. He wasn’t sure what was unfolding here, but his growing sense of dread argued that it was not anything good.

The automaton walked smoothly past the audience seated in rows. The gas lamps attached to the walls left an area of relative darkness directly below them; the automaton stayed in the shadows — it was impossible to discern whether this was by intention or pure happenstance. Thanks to the uneven lighting, in any case, the automaton remained largely unnoticed. But Ronald had seen exactly where Elektra was, and was running after the machine as fast as he could go. Elektra reached the final row of seats and halted. The automaton stopped dead, then turned to its left; each motion was separate, machinelike, although entirely smooth and silent. Next it walked forward again, immediately behind the chairs. Ronald was halfway there, and nearly stumbled over a cane one of the inventors had left leaning against the wall. Elektra halted again, this time immediately behind Doctor Witherspoon’s chair. The doctor was still standing, addressing Professor Q in loud, accusatory tones. The automaton pivoted to face Witherspoon’s back. Ronald skidded around the last row of seats just as two gleaming metal arms began to reach out toward Witherspoon, who was still unaware that the automaton was mere inches away.

The automaton’s metal hands touched Witherspoon’s shoulders. The doctor, feeling the touch, faltered in his diatribe and began to turn to see who was there. Just at that second Ronald arrived, skidding to a stop beside Elektra. He firmly grasped the automaton’s arms, trying to raise them away from Witherspoon.

The automaton turned its head toward Ronald and spoke in its otherworldly voice. “Ronald. Please do not interfere with my objective.”

Ronald thought fast. “Elektra, what is your objective?”

“Objective two point three one, subsumed under protection sub bodily sub professor. An event potentially damaging to Professor Q is presently likely. Intercession to redirect the outcome of the event is the immediate objective.”

“Elektra,” said Ronald, “objective achieved.”

Doctor Witherspoon had turned completely around by this point, and was staring wide-eyed at the automaton and at Ronald. The automaton regarded him blankly. In the lower lighting at the back of the hall the slight glow in its eyes could be clearly seen. The automaton did nothing for a moment, then lowered its arms to its sides. “Agreed, Ronald,” came the disconcerting voice, “outcome has been redirected. Potential for damage is now considered negligible.”

Ronald heaved a sigh. He wasn’t sure what Elektra had been about to do, but earlier that same day he had completed a set of tests of the automaton’s lifting ability. The machine was capable of lifting several tons without stressing its primary structure. In short, it was enormously strong. Ronald knew there was, somewhere deep within Elektra, a set of what the professor called “ethical protocols” that should prevent the machine from accidentally harming anyone. But the professor had never shared the details of how that subsystem worked, and Ronald had never been asked to test it. But whatever Elektra had been about to do, it hadn’t appeared to be “accidental” at all.

Witherspoon recovered himself as soon as he saw that Ronald had intervened with the automaton. He turned back to the podium.

“This ‘automaton’ is clearly a fraud,” he called. “Professor Q, you have outdone yourself in deception! I demand that you reveal the human operator concealed within that cunningly constructed metal costume!”

The audience, on cue, swiveled their attention to the podium where the professor stood, still bright red and visibly trembling in outrage.

“A fraud, you say?” he roared at Witherspoon, “and this accusation comes from an interloper who gained entrance to this gathering only by donning a deception of his own? This, sir, is only the latest outrage from you! I shall demonstrate, sir, the authenticity of my work, and then, sir, I shall demand your expulsion from this organization!”

There were gasps from the crowd. No inventor had been ousted from the club since the episode, several years ago, of an inventor named Hugo who had specialized in odd machines that never quite worked, but had been revealed to be simply copies of ancient Perenthian devices (of unknown application) discovered by a relative of his who had journeyed to the Mervesi Islands.

The Professor’s Demonstration

Professor Q marched rapidly to the last row of chairs where Ronald and the automaton were still standing. “Ah, Ronald, excellent,” he said. “Please clear the items from that table, and cover it with a suitable cloth.”

Ronald trotted to the table the professor had indicated and began removing several ornamental vases. One of the club’s butlers arrived, efficient as always, carrying a linen tablecloth that he helped Ronald drape across the heavy wooden table. The professor and Elektra stepped to the table, the professor turning to address the audience, who were leaving their seats to gather around this next stage of what had turned out to be a very entertaining evening.

“Gentlemen,” said Professor Q, “although there should be no need for such antics, I shall now, simply for your edification, demonstrate that this device is as I say. Moreover, I shall direct the automaton to conduct the demonstration itself.”

There was much shuffling as everyone strove for the best view. Several muffled exclamations suggested elbows were being actively employed. At least three inventors produced pocket notebooks in which they jotted down the ideas they had just had regarding devices to enhance viewing from amidst a crowd.

“Elektra,” said the professor, “be extremely careful in carrying out these next tasks. Take every precaution to avoid throwing your delicate mechanisms out of balance.”

“I shall comply,” came the response.

“Elektra,” said the professor, turning to make sure he (and the automaton, of course) occupied the center of attention, “remove your head and place it on the table.”

There were audible gasps from the crowd as the automaton deftly swiveled two latches at the base of its neck, grasped its head in its hands, and turning it exactly ninety degrees, lifted it off its shoulders and placed the head on the table. The base of the neck flared out to meet the shoulders, and the flared portion served admirably as a base for the head. There were more gasps from the crowd when the head, from its position on the table, said “Task complete.”

“Excellent,” said Professor Q, checking the crowd surreptitiously once more. “Now, Elektra, seat your torso on the table, detach your legs, and place each leg on the table separately.”

The automaton did so. “Elektra,” the professor directed, “now detach your upper torso unit from the lower unit and use your arms to place the upper unit beside the lower unit.”

The crowd had no more gasps left to give as the automaton flipped hidden latches, revealing a seam approximately at its waistline. It then placed its hands on the table and pushed downward, raising the top half of its torso off the bottom half. It proceeded to use its hands to walk the top part of its torso to the side, then set that unit down onto the table.

“Gentlemen,” said the professor triumphantly, “As you can see, the automaton conceals nothing other than the internal mechanisms, designed and executed by myself, that motivate it. The ectonic energy that motivates Elektra has a limited range, but it is sufficient for one more demonstration. Elektra, wiggle your left foot.”

The foot on one of the detached legs wiggled. “Even partially dismantled, the automaton retains many of its capabilities,” smirked the professor. Ronald, who had himself directed this process repeatedly back in the laboratory, shifted his weight nervously from side to side. It wasn’t unusual for something to go wrong during the reassembly process, and the professor’s resulting tirades were acutely unpleasant.

“President Edwards,” said the professor, peering around until he located the club president. The man looked even more nervous than Ronald felt. “I believe I have refuted the foul accusation that was directed at myself and my work moments ago. I now demand that my tormentor be escorted from these premises and categorically disallowed from readmission!”

“I…er…that is…” stammered Edwards.

“There is no need,” shouted Witherspoon, shouldering his way to the front of the crowd. “I willingly quit this tawdry scene! I leave you, ‘professor’…” Witherspoon’s voice dripped with disdain, “with this.”

Witherspoon took a small brass device from a pocket. It resembled a bulky pocket watch with a short metal pole extending from where the stem would have been positioned. He pressed a stud on the side of the device, then turned a dial on the face of the thing. It clicked audibly, then a tiny bell rang from within. Rather than dying away, the pure tone grew in volume until everyone in the room — other than Witherspoon himself — covered their ears against the pain. As the sound grew louder, several of the older members worried that their remaining teeth would be vibrated out of their skulls. Two members’ monocles cracked. Then the sound was instantly gone. Everyone slowly looked up, taking their hands from their ears. Witherspoon had disappeared without a trace. Ronald, suddenly suspicious, spun to look at the disassembled components of the automaton on the table. The light emanating from the device’s eyes had gone out. He touched the metal hand nearest to him — it was entirely inert. The automaton was inoperable. The piercing sound from Witherspoon’s device must have done its worst to the sensitive gears and workings within Elektra.

“That meddlesome villain!” cried Professor Q, realizing what had happened. “This is the final outrage. Ronald, carefully pack up these components and transport them back to our laboratory. Gentlemen, as you must recognize, I must take my leave to repair the damage inflicted on my automaton. I look forward to greeting you at our next meeting. Good Evening.”

With that, Professor Q swept dramatically out of the hall. The crowd of inventors broke up into groups of twos and threes, discussing the astonishing events of the evening. Many heads could be seen being shaken, whether in disbelief at the open display of hostility or in admiration for the inventive genius they had seen — as some admitted, from both sides of the conflict. Ronald was left to fetch shipping crates, stuff them with soft wool, and gently prepare the inert components of the automaton for shipment back to the laboratory. Ever efficient, the club’s staff of butlers were quite helpful in the process.