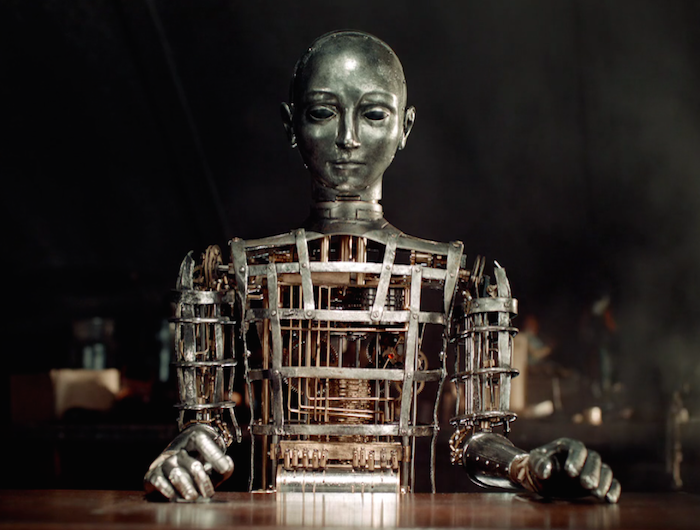

Ronald stayed up far into the night studying the automaton’s description of the system that powered it. It had been Professor Q’s innovation, and one which he had not shared with Ronald. Still, he wanted to present the professor with the solution to the puzzle of how Doctor Witherspoon’s pocketwatch-sized device had disabled Elektra. Ronald felt sure the answer lay somewhere in the mechanism the professor had described as being powered by “ectonic energy”.

The automaton had provided very thorough notes about its locomotive unit, but Ronald had difficulty grasping several points. The energy itself was transformed by an oddly-shaped device called the “beryllium actuator” — the transformation was from the native “ectonic energy” to the linear power that manifested in the motions of the automaton’s arms, legs, and other subsystems. Yet the “ectonic energy” itself remained a mystery to Ronald. It seemed to be focused by the spherical casing around the actuator, but where did it come from? And what was it? The automaton’s notes said only “ectonic energy is radiational in nature and invisible to human senses, but is available in ample supply in any location.”

Ronald supposed that Professor Q had come up with the name “ectonic energy,” but the name held no clue to the nature of the phenomenon. Ronald sat back from his small desk, rubbing his head. He was still certain there was something about the energy source, or perhaps the transformation system, that was vulnerable to the piercing, high-frequency sound emitted by the doctor’s device. But without understanding anything about the energy source itself, he found himself stymied. Feeling cold, he got up to put another small shovelful of coal into his stove.

As he did, Ronald noted idly that the fire in the stove had not yet died down especially. Suddenly curious, he waved his hand nearer the stove. He couldn’t be sure, but for some reason he had the impression it was not as hot as usual, which would explain why he had felt a chill. He snapped his fingers — he was, after all, a laboratory assistant, and there was a fully equipped inventor’s laboratory just outside his door. He might not yet understand ectonic energy, but he could at least apply himself to this small conundrum. He quickly went out to the lab, fetched the smallest thermometer he could find, and placed it on the stove. As its indicator climbed, he took from his personal bookshelf one of the standard references anyone working in a modern laboratory needed: Cruikshanks’ Referential Handbook. “Cruikshanks,” as everyone called it, was a bound book listing all the temperatures, weights, material properties, conversion factors, tables of calculations, and other handy facts one would need in the course of experimentation. He thumbed through it to find the properties of coal. There it was: coal burned at an average temperature of 874°B. He checked the thermometer, which read only 731°B. He waited few moments — perhaps the thermometer hadn’t reached its full temperature yet? But no, there was no change. He changed the position of the device, thinking it might be on a cooler spot on the top of the stove. No matter where he positioned the thermometer, though, Ronald was unable to find a spot where the reading was higher than 733°B.

Professor Q entered the lab the following morning to find four stoves burning, thermometers attached to all of them, and Ronald annotating a table of numbers in his notebook. “What’s all this?” he asked mildly.

Ronald turned to him, eyes bleary from a sleepless night. “Professor,” he said, “there’s something wrong with our coal. It’s burning at a lower temperature than it should.”

“A bad shipment?” asked the professor.

“I don’t think so,” said Ronald, “I dug out some of the oldest from our scuttle, and compared it with some of the newest; it’s all the same. The temperature is down an average of 141°B from what Cruikshanks says it should be. The findings are consistent.”

“How odd,” said the professor, “that suggest that our consumption…”

“Yes,” said Ronald. He had already followed that line of reasoning. “I checked the books and our consumption is up.”

“It may be time to cancel our contract with Throckmorton’s,” said the professor, naming their longtime supplier.

“Professor,” said Ronald, “it’s not just coal. That stove over there is burning seasoned hardwood, and the temperature of that is lower than it should be as well. And the gas in the lamps is burning at 650° instead of the 720° it says in Cruikshanks.”

“Fascinating,” said the professor. “Ronald, we must investigate this further. Take some thermometers and and travel by train to…well, it doesn’t matter as long as you go far enough. Choose a line and go to the end, then replicate the experiment there. I shall visit the offices of companies that buy and sell a great deal of coal or gas and attempt to ascertain their recent experiences. Not a moment to waste; let us be off!”