One of the tropes of cowboy movies is the poker game in the saloon. Depending on the movie, the game might show off the skills of the hero, unmask the villain’s fruitless attempts at cheating, or simply provide a way to gather the important characters into one location so that when another important character walks in, the cameras can catch all the important action from only two angles.

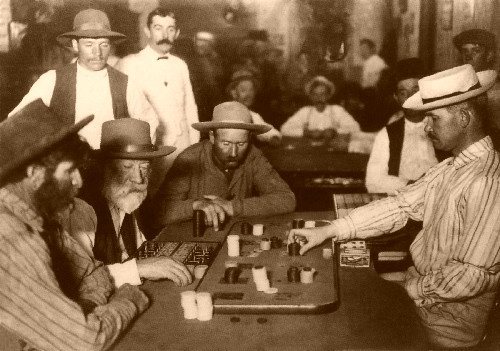

But there’s something wrong with the whole idea. In the American west in the 1800s, the card game played in saloons was far more likely to be Faro, not poker. Faro, which is a shortened version of “Pharoah,” the original French game, was enormously popular in the 19th century. It’s played with cards and a thing resembling an abacus, called the “case.” It’s a gambling game, but beyond that the details aren’t important here.

What we’re really interested in is that Faro was so popular that it contributed a number of phrases to English. Most of them have disappeared along with the game, but “play both ends against the middle” still turns up here and there. Another phrase — this one is defunct — was “keeping cases.” The “case” in Faro was for keeping track of the cards as they were dealt (one player was designated the “case keeper.” Because one method of cheating was to misrepresent the count (indicated by the abacus beads on the case), experienced players would “keep cases,” meaning they kept their own count of the cards. “Keeping cases” came to mean paying close attention to something.

If you were going to effectively cheat in a Faro game, you really needed two players working together. One would deal the cards (from another piece of equipment, the “shoe”) and the other would manipulate the case. Those two players had to cooperate in their illicit activity — their “joint endeavor” — to succeed.

Any team of two can accomplish a lot in the way of nefarious activities, particularly in a location where everybody else (1) has some money, and (2) is drinking. “Joint endeavors” happening in bars and saloons was such a common thing that the establishments themselves began to be called “joints.” The term stuck, and “joint” became a slang term for just about any building or location.

“Keeping cases” eventually turned into something shorter: “casing.” And in 1926, a police report in West Virginia included this: “No one would suspect that the well-dressed young man who had made a purchase just at closing time prior to the burglary was “casing the joint.”

As far as anybody knows, that’s the first time “casing the joint” appeared in print. Just in time, too, because movies in 1926 were just on the verge of becoming “talkies” (the first big “talking picture” hit, “The Jazz Singer,” debuted in 1927). And then along came another movie genre — gangster films. And along with them came another trope: “casing the joint.”

A Faro game in an Arizona saloon in 1895.