Today we remember two aircraft designers — one quite mainstream, and the other controversial and somewhere outside the conventional history of aeronautics. First up is Henri Coandă, who was born June 7, 1886 in Bucharest, Romania. In 1909 he enrolled in a brand-new school in Paris teaching aeronautical engineering, and graduated at the head of the school’s first class. The very next year he designed and built the Coandă-1910, a very unusual airplane even for those days, when airplane design was not yet standardized.

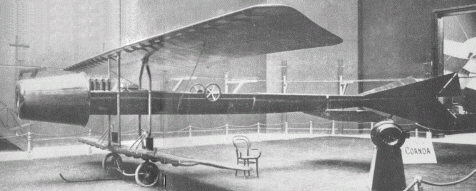

The Coandă-1910 was not a biplane; it was a “sesquiplane,” which meant that it had two wings but the lower one was less than half the size of the upper one. And it didn’t have a propeller. Coandă had devised a weird-for-the-time ducted engine that looks, to modern eyes, very much like a turbofan jet engine. The Coandă-1910 also had a very long, thin fuselage, and a tail structure more like a missile than an airplane.

The Coandă-1910 was the only exhibit at the 1910 International Aeronautical Exhibition in Paris that didn’t have a propeller, and there was controversy about it from the start. For one thing, nobody quite understood how the ducted engine was supposed to work, or if it even did. For another, it looked so different from other aircraft at the show that there was doubt about whether it could actually fly. Coandă said it did; he had tested it, but he didn’t have evidence — or at least not enough evidence to convince everybody. He didn’t have much luck explaining his engine either, although years later when jet engines became mainstream, Coandă brought out his original plans and pointed out that really, his 1910 engine was the world’s first jet engine. Critics claimed otherwise. Unfortunately, the Coandă-1910 was no longer around to demonstrate how it worked. There was controversy about that, too. Coandă said he was flying in it late in 1910 and crashed, and the plane was destroyed. But once again, he didn’t produce a lot of evidence.

Coanda might have had more success if he’d stuck with the Coandă-1910 design and built later versions, but he’d moved on to other projects, including research (the Coandă effect in fluid dynamics is named for him) and another approach to flight: a “flying saucer.” He also designed and built snowmobiles, of all things. Nobody is 100% sure how successful his original airplane was, but in 2010 Romania celebrated the centennial of jet aircraft based on the Coandă-1910. They issued a stamp and a coin featuring Coandă, and started on a working replica of the Coandă-1910. It’s unclear whether the replica was ever finished.

Meanwhile, when Henri Coandă was just 8 years old (in fact on his birthday), Alexander de Seversky was born in the Russian Empire, in what is now Georgia. His father owned one of the first airplanes in Russia, and Seversky was a pilot by the age of 14. He earned an engineering degree and enlisted in the navy, becoming a Naval aviator. During World War I, he was shot down and although he survived the crash, he lost his leg. They wouldn’t let him back in the airplanes, so he appeared at a local air show and performed aerobatics, just to prove to his superiors he could do it. They were not impressed, and arrested him instead. But the Tsar intervened personally and ordered Seversky reinstated as a pilot. That worked out, as Seversky became one of the top Russian aces of World War I.

After the war he was stationed in the US as part of the Russian Naval Aviation Mission. After the 1917 revolution, though, he decided to stay in the US. He became a consulting engineer and his name is on 364 patent applications for various aeronautical advances. He invented the first working system for refueling bombers in the air, and also invented the first bomb sight stabilized by gyroscope.

Seversky received a large payout for his bomb sight invention, and founded Seversky Aircraft Corporation in 1923. The company manufactured parts and instruments rather than whole airplanes, and was wiped out by the 1929 stock market crash. Seversky managed to recreate it, though, with the backing of investors, and the second iteration of the Seversky Aircraft Corporation focused on research and design. They build the SEV-3, an innovative, all-metal airplane that set several speed records, usually piloted by Seversky himself. The company renamed itself the Republic Aviation Corporation in 1939, and produced the P-47 Thunderbolt military airplane during World War II.

Seversky himself moved on to more strategic concerns, and published the book Victory Through Air Power in 1942. It was a serious book, and also became a best seller — oddly enough Walt Disney produced an animated film based on it. He became a consultant to the US war effort and advised about air power and airplane-based weapons. He also kept designing, and in 1964 proposed the Ionocraft, which was supposed to be a one-man airplane powered by an electrical discharge that produced an ionic wind. He built a working model, but found that the power requirements for a man-sized version were more than any existing system could produce. In 2018, though, a team from MIT demonstrated an airplane using the same power system.

Seversky wrote additional books about military aviation, and helped found the New York Institute of Technology. One of their buildings is called the DeSeversky Center.

Coandă-1910 at the 1910 Paris Air Show

Republic P-47 by Tim Felce – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83980094