Some cities grow organically, but others are designed. One of the “designed” cities is Washington, D.C., the US capital. It was designed based on the L’Enfant Plan, created by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, who was born August 2, 1754 in Paris.

L’Enfant’s father, also named Pierre, was a professor at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, and when the younger L’Enfant was about 17, he enrolled in the same academy. In fact, his father was one of his teachers. It was apparently a pretty good place to study art; many of the classes were held in the Louvre, which was nearby. L’Enfant probably studied urban planning at school, since the curriculum covered baroque plans for Rome drawn up by Domenico Fontana, and for London, by Christopher Wren.

After L’Enfant graduated in 1776 he was recruited to serve in the army — but not to serve in France; he served as a military engineer in the Continental Army in the American Revolution, where France was supporting the colonial side. He served with Major General Lafayette, the highest ranking French officer in that war.

L’Enfant also served on General George Washington’s personal staff, and painted a portrait of Washington. He also painted two (or possibly more) panoramas of Continental Army encampments, including one of Washington’s tent. It’s the only known depiction of that tent, and now hangs in the Museum of American Revolution in Philadelphia. You can’t miss it; it’s over two meters long.

L’Enfant served in battle as well, and was wounded at the Siege of Savannah in 1779. He was taken prisoner in Charlston in 1780, and returned to the Continental Army in a prisoner exchange. Nobody is quite sure, but sometime around 1782 he may have designed the medal now known in the US as the Purple Heart.

In 1783 the Continental Army was disbanded and L’Enfant was awarded 300 acres of land in what is now Ohio. The deed was signed by then-president Thomas Jefferson. But L’Enfant never even visited the land; instead he settled in New York City and worked as an architect and designer. He designed the New York City Hall, which is still there, now known as Federal Hall. He also designed various houses for wealthy New Yorkers, as well as some of the furniture in the houses. He also designed coins and medals, including the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati. The Society of the Cincinnati was an organization of former officers from the Continental Army. L’Enfant not only designed the badge; he was one of the organization’s founders.

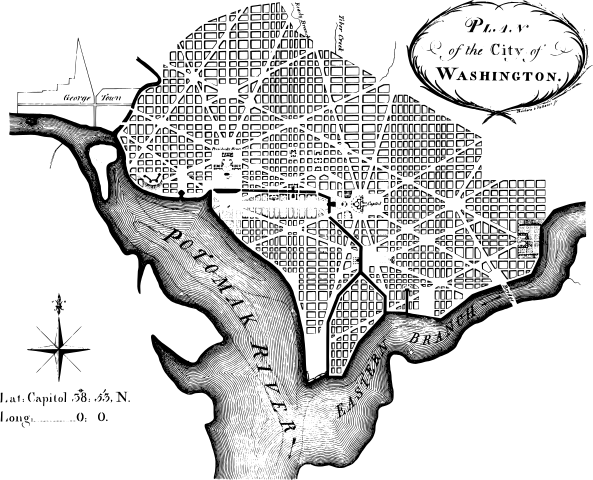

L’Enfant’s penchant for never visiting land that he owned continued in 1787 when he inherited a farm in Normandy, France. As far as anybody knows, he never set foot on it. But he did visit the site where the “Federal City” was to be built. The whole thing began in 1790 when the Congress passed the “Residence Act,” designating a new capital city to be built next to the Potomac River. The location was the result of a number of political compromises, and by any objective measure was an awful place to build a city. It was essentially a swamp (and if you’ve ever visited Washington, D.C. in the summer, you’ll know how much it still feels like a hot, humid swamp). L’Enfant got the appointment to design the city in March, 1791, and presented his first plan in June. The place was intended to be big; the size of New York, Boston, and Philadelphia combined, with space for a million residents.

L’Enfant chose “Jenkins Hill” as the site for “Congress House” (now known as the Capitol Building), describing it as “a pedestal awaiting a monument.” He didn’t design the building itself — that was Stephen Hallet — but his notes include sketches that Hallet almost certainly incorporated in the design. L’Enfant did design the “President’s House” (now known as the White House), but his design was never built. He thought the place should be more of a palace than just a house, and specified a building five times the size of what it is today.

However, a huge project directed by politicians is not a recipe for success, and L’Enfant was so frustrated that he was eventually dismissed. Isaac Briggs took over — but he didn’t last. Benjamin Ellicott got the job. Then Joseph Ellicott, Thomas Freeman, Nicholas King (twice), and Robert King, Sr. took turns trying to lead the project. Finally, in 1802, Thomas Jefferson got rid of the whole organization and appointed three people who reported directly to him rather than to Congress.

L’Enfant proceeded to design Paterson, New Jersey, a mansion in Philadelphia, and Fort Mifflin near Philadelphia. Other cities, including Brasilia, New Delhi, Canberra, Detroit, Indianapolis, and Sacramento have been designed based on L’Enfant’s plans for Washington, D.C. L’Enfant died in 1825, when the capital city still wasn’t finished. Even then, it was neglected for decades. The Washington Monument was begun but unfinished for many years, and surrounded by untended fields where animals grazed. Today that area is the Mall, where you might see some pampered pets but no sheep or cattle. Washington D.C. was called “The City of Magnificent Intentions” by Charles Dickens, who noticed that many streets weren’t complete and buildings were unfinished. Finally in 1871, after the Civil War, the US government began to pay attention to the city and began paving roads and installing infrastructure. In 1909, when the city began to resemble the showpiece it’s intended to be today, L’Enfant was exhumed and reburied in Arlington National Cemetery, where he’s commemorated by a monument.

L’Enfant’s plan, with some enhancements by Andrew Ellicott