When you were a child, if your mom pretended to have a disability, went to a faith healer show, and jumped up yelling about being healed — and she she staged the whole thing as a practical joke — what do you think you might grow up to become? In the case of James Thurber, whose mother did exactly that, you’d become one of the most popular humorists of your era.

Thurber was born December 8, 1894, in Columbus, Ohio in the US. Both of his parents influenced his work, and he described his mother as “one of the finest comic talents I have ever known.” Thurber’s own childhood was notable for a game of “William Tell” he played with his brother when he was seven years old. Instead of shooting an arrow into the apple on James’ head, the arrow hit James in the eye. He lost the eye, and his limited vision affected him in two major ways: he was unable to play sports as a boy, and he was barred from graduating from Ohio State University in 1918 because he was unable to see well enough to complete the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) course, which was mandatory.

Thurber did manage to work as a code clerk for the US Department of State after leaving college, which took him to Washington, D.C. and to Paris. In 1921 he returned to his home town and became a reporter for The Columbus Dispatch newspaper. In addition to reporting, he wrote a weekly column titled Credos and Curios, where he reviewed books, plays, and movies. He also returned to Paris as a reporter, and wrote for several newspapers besides The Columbus Dispatch.

At some point he met the writer E.B. White, who helped Thurber decide to move to New York City in 1925. White helped him join the staff of The New Yorker magazine, where he started as an editor. His later fame included cartoons that he drew, and that career is also thanks to White, who found some of Thurber’s pencil drawings, added ink, and submitted them to the magazine. The New Yorker published Thurber’s cartoons, and Thurber went on to shift from being an editor at the magazine to being one of the major contributors, publishing stories and drawings for decades. He and White continued to collaborate on some projects, although White at least once said he regretted having inked-in those original found drawings. He might have felt that he meddled too much in Thurber’s work.

Thurber primarily wrote humorous short stories, often inspired by events in his own life. He wrote some longer works as well, including The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which has been adapted to film twice, in 1947 and 2013. Other Thurber titles have been filmed too, including The Male Animal and The Catbird Seat (the movie’s title was The Battle of the Sexes).

In addition to short stories and books, Thurber wrote fairy tales, sometimes book-length (The White Deer, The 13 Clocks, and The Wonderful O). Besides that, he wrote over 75 fables, which are collected in the books Fables for Our Time and Famous Poems Illustrated, and Further Fables for Our Time. As fables, they usually featured talking animals as main characters and ended with some sort of moral — which, since they were written by Thurber, might be pretty funny.

Nearer the end of his writing career, Thurber added essays about the English language to his New Yorker repertoire. He complained about casual expression in The Spreading ‘You Know,’ and added similar commentary in The New Vocaularianism and What Do You Mean It Was Brillig?

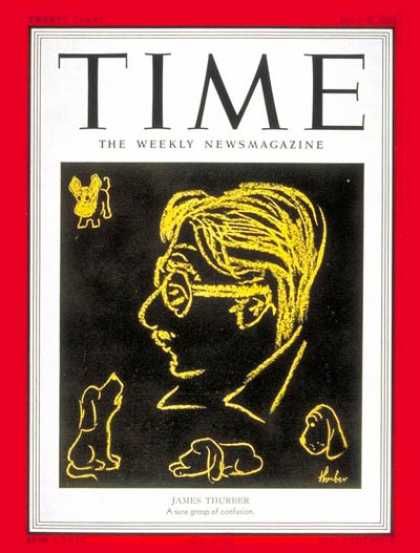

In his last twenty years or so, Thurber had to change the way he worked because his eyesight was failing (thanks to that childhood incident), and he became nearly blind. He still drew cartoons, but began using a thick black crayon on a very large sheet of paper. He could still draw though, and several of his cartoons became cover illustrations for The New Yorker. His very last completed drawing was a self portrait that became the cover of Time magazine on July 9, 1951. You can also see it on the dust jacket of The Thurber Album, published in 1952.

Thurber is still an inspiration for many, and you can see evidence of that in the 2021 file The French Dispatch, which includes him in the end credits. He was also mentioned in an episode of the Seinfeld TV series, and in a video podcast by comedian Norm Macdonald, Larry Miller (another comedian) mentioned that Thurber was his biggest influence.

Thurber published about 20 books, and nearly as many again have been published posthumously. He also wrote children’s books, and two plays. In addition to that, he wrote an enormous number of short stories, most of which were published in The New Yorker. And thanks to Thurber, “Walter Mitty” has entered English as a generic description of a meek character whose fantasy life is richer and more compelling than his daily existence. Like a lot of humor that proves to have lasting value, the funny surface of Thurber’s story lies atop a more serious and darker message. Maybe we laugh because underneath, it hurts.

Thurber’s self-portrait on the cover of Time magazine.