Walker Evans was an American photographer born October 3, 1903. His best known work is from the Great Depression of the 1930s, when he was part of the US government-funded project to send writers and photographers around the country to chronicle and document life in the nation.

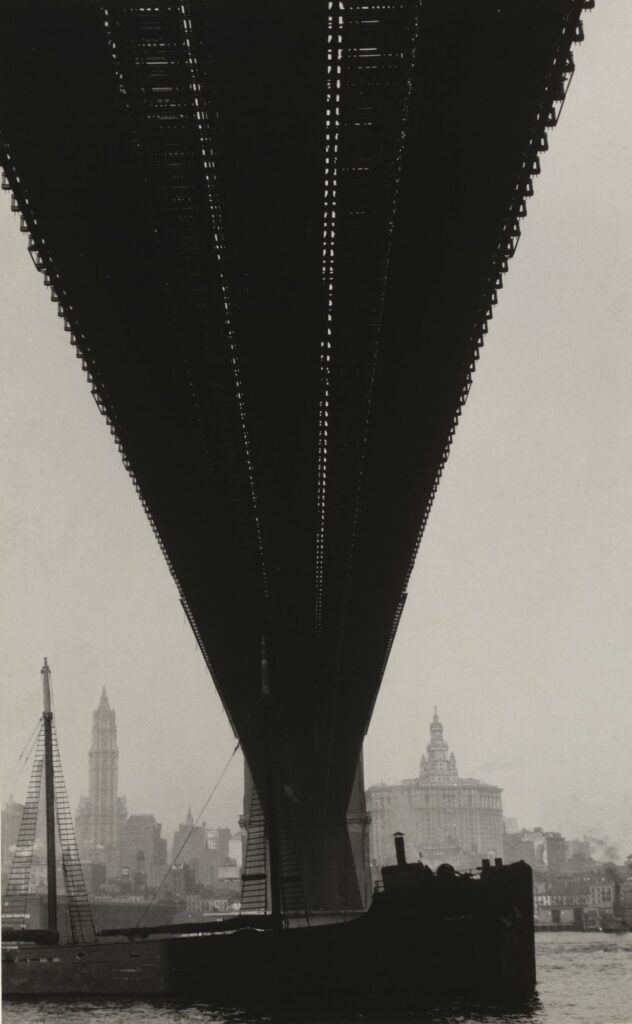

Evans wasn’t a street photographer; he used an 8×10 inch view camera that must have been quite a project to lug around and set up. Not to mention composing; you see everything upside-down when you’re choosing your image. He managed pretty well, though, and had the goal of creating photos that were “literate, authoritative, and transcendent.” His photographs record bleak rural poverty and equally bleak urban industrial landscapes, but Evans himself was raised in a pretty wealthy family. In the 1920s he spent a year in Paris, rubbing shoulders with the artistic and literary community there, then returned to New York in 1926 and joined the same sort of group there. And he wasn’t an artist of any sort at the time; he was a clerk in a stockbrokerage company.

He didn’t start exploring photography until 1928, when he was 25. But within two years he was publishing his pictures in various books. Then he got an assignment from a publisher to travel to Cuba to take photos to accompany a book they were planning to publish. He met Ernest Hemingway there, and gave him some of the photos — they weren’t rediscovered until 2002 in Hemingway’s former house in the Florida Keys.

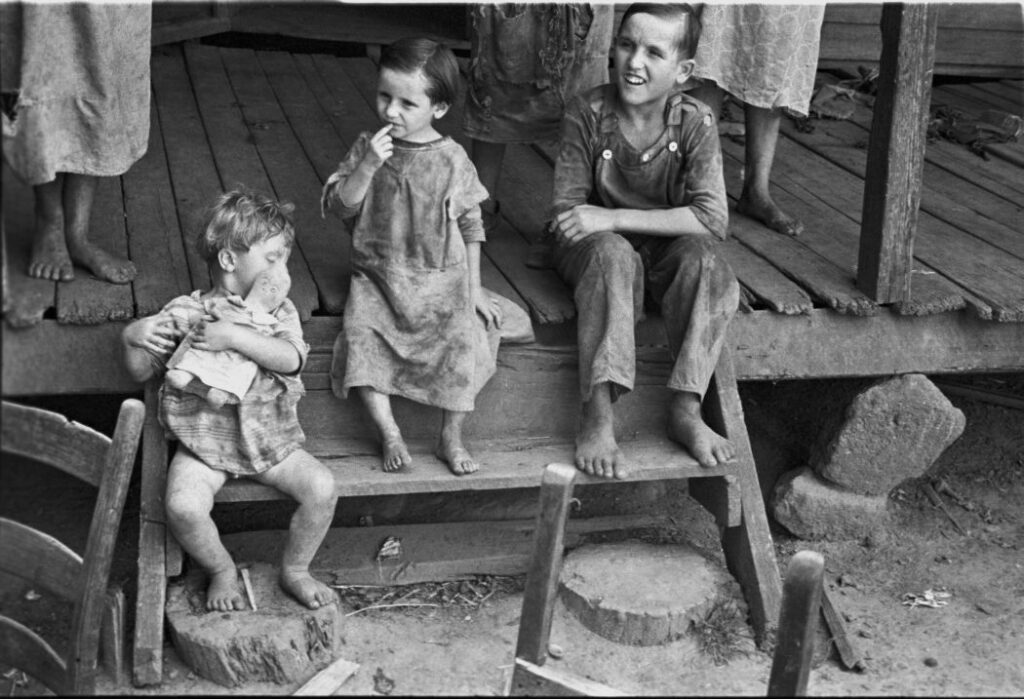

During the Great Depression, he was hired by the Department of the Interior and the Farm Security Administration to take photos in Pennsylvania and the southern US. Some of his most famous photos are from that period, as well as his work with writer James Agee on the book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men — it was a study of tenant farmers, who were even more poverty-stricken in the 1930s than usual. They focused on three families, and Evans’ photos show them with gaunt faces, living in shacks in the midst of bare, dusty wasteland. The families themselves, though, turned out to be angry at both Agee and Evans — for not giving them copies of the book, and for depicting them as though “they couldn’t do any better, that they were doomed, ignorant.”

Although most photographers in that era worked with the camera and in the darkroom, developing their own film and making prints, Evans typically let assistants do all the darkroom work, and hardly supervised it. The most he would do was pass along a few notes.

He was a writer too, and worked on the editorial staff of Time and Fortune magazines in the 1940s and 1950s. And he moved on from his view camera; in the 1960s he used small-format cameras, and in the early 1970s he did projects with Polaroid cameras. It was a sponsorship deal; the Polaroid company gave him an unlimited supply of film and cameras. At the time he was in his 70s, and said it was easier to work with such a simple-to-use camera.

In 1975 he was working with the author Hank O’Neal on a book, and they were trying to find a specific photograph — of Evans himself — for the back cover. One night Evans called O’Neal to tell him he’d found the picture. They made plans for their next meeting. Then in the morning one of O’Neal’s colleagues said “Isn’t it terrible about Walker Evans?” He’d died that night, right after speaking with O’Neal.