Doctor Witherspoon, having arisen at his usual hour and dawdled over his newspaper, his breakfast, and the day’s wardrobe, was forced to ask the driver of the steam taxi to hurry to Harrow’s in order not to be late to his first appointment. Harrow’s was the financial institution — considerably more than just a bank, as they were at pains to explain to prospective clientele — where the doctor kept his considerable financial assets. Some were in the massive vault far below the floor of the opulent lobby. But the majority of his assets existed in the endless columns of figures constantly totaled, checked, and updated by the small army of clerks housed in a nearby building that boasted far fewer amenities than did the headquarters of the establishment.

Witherspoon’s appointment was with Plattsgivens, the balding, nondescript manager who had met with him each quarter to report on his accounts ever since the doctor had walked in years ago clutching the strongbox containing the remains of the family fortune. He hadn’t been an eccentric inventor in those days; far from it. He was simply a young heir and the sole survivor of a boating mishap in which his father, mother, and sister had drowned. His own role in the accident, which had resulted from an explosion in the steam propulsion unit he had built himself, had never been recognized. Quite the opposite; he was a young man merely months away from his majority, cruelly orphaned by an unforeseeable and unavoidable accident.

Far from being dissuaded from his hobby of tinkering, his newfound independence had enabled him to indulge his interests more than ever. Armed with the funds provided by the contents of the family coffers and augmented by the proceeds from the sale of the family estate — a place in the country so isolated that he loathed the idea of ever setting foot on the grounds again — Witherspoon had found his way immediately to the bustle and excitement of Byronton, and had turned his attention and his not-inconsiderable talents at finance and business toward the objective of constructing what he thought of as his “Byronton self” — recognized inventor and admired eccentric.

He had adopted the “doctor” nearly immediately. He was not, of course, any sort of real doctor any more than the several “professors” in the Inventors Club held actual professorships. Other than Professor Q, of course, who taught at Byronton University. His bona fides as an inventor were easily established by a careful search for young tinkerers not so different from himself, other than being clearly more talented. They were nearly always penniless, and so quite susceptible to his offers to fund their projects. In the course of things he would befriend them. Intimate chats over pints at the alehouse (all rounds purchased by Witherspoon, naturally) would lead to learning most, if not all the details of the inventions being pursued. After that, further funding would require signing some simple papers, drawn up by the attorneys the Witherspoon fortune could easily afford. Then, in the best case, the invention would be finished and the proud creator would rapidly learn what had really been in the contract he had signed. All rights belonged to Witherspoon, and the actual inventor was barred from ever revealing his involvement. The payments were generous, particularly at first, and some of the tinkerers found that they didn’t even mind giving up the recognition in exchange for a comfortable life and a well-stocked workshop, even if it did have to be located well outside the city. Those who did mind soon found that the legal talents of the Witherspoon attorneys had crafted a well-nigh unbreakable contract.

Witherspoon always adhered to his side of the deals scrupulously. To fail to do so might open an avenue for the actual inventors to pursue their own notoriety, which certainly couldn’t be allowed. Besides that, he really did admire their abilities, and since he owned the rights to any future inventions, not to mention royalties that might ensue, he had an interest in keeping them as happy and productive as possible.

Interest on the original assets, royalties on the growing number of useful innovations, and the lucrative investments managed by Plattsgivens (with cogent guidance from Witherspoon himself; although he was only modestly capable as an inventor, he was an extremely able financier) made it possible to support a slowly growing list of tinkerers, even if some of them had yet to produce a return.

Following his meeting with Plattsgivens at Harrow’s, which was wholly satisfactory, Witherspoon proceeded to Filson and Nobbs Mercantile where he made some fairly extravagant purchases on behalf of Fritz and Imelda. Most of what he bought they had requested, but as always he added some items he simply thought they would appreciate. Witherspoon’s relationship with Fritz and Imelda was not at all the same as he had with his cadre of tinkerers. They had entered his employ after he had begun to become established in Byronton and had even opened his own laboratory. In his provisional membership in the Inventors Club he had learned that the laboratory was expected of members, and that nearly all members employed assistants, some of whom were spoken of with great respect. Many of the laboratory assistants might have qualified as Club members in their own rights had they not been disqualified by reasons of gender, nationality, or in one or two cases some essential uncertainty about their basic humanity. Fantastical and arguably mythic creatures such as elves, trolls, dwarves, and even golems enjoyed no formal recognition in Byronton, even among members of the Alchemists’ Society (whose standards, according to most other similar groups, were simply an embarrassment), but in the teeming centers of the most cosmopolitan city in the world one might notice, not infrequently, the occasional individual whose appearance invited either consternation or wonderment, depending on who might be doing the noticing.

Fritz and Imelda were different. They had presented themselves at the door of Witherspoon’s new laboratory practically as soon as he had formally opened it. The rich tradition of inventing in Byronton dictated a brief ceremony whenever an inventor dedicated a new laboratory; the Minister of Creations would make a perfunctory speech, present the proprietor of the new lab with an official paper declaring something (no one was sure about the declaration because no one had ever actually read it), and then the half dozen or so Byrontonians who had shown up would retire to the nearest alehouse to toast the newly minted inventor — who, also by tradition, always bought the first round. Fritz and Imelda had not attended Witherspoon’s ceremony, but might have been watching from nearby, since the moment he returned from the Cog and Spindle, where the celebration was just getting started, they appeared on his new doorstep.

“New laboratory need new assistants,” Imelda had said. “I am Imelda, husband is Fritz. We are team. You hire?”

“Well, er…” Witherspoon had sputtered. He hadn’t expected to even begin looking for a lab assistant until the following day. “Do you…that is, are you experienced in the…er…job?”

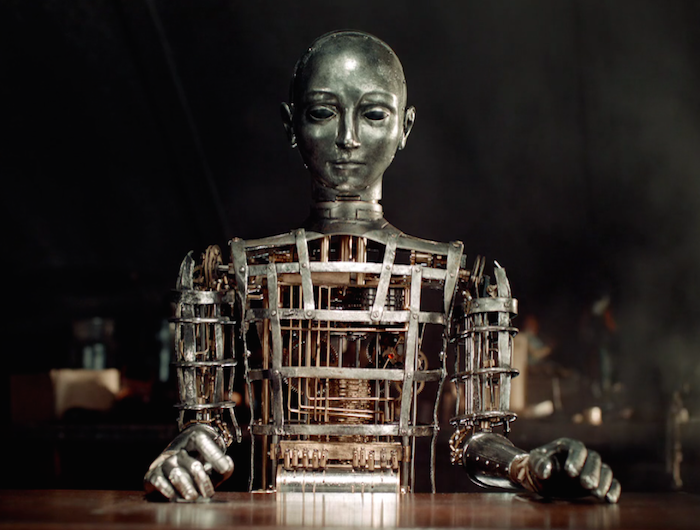

Fritz had smiled and gestured at the small leather case he was carrying. “Can show. Have table?”

They had entered the new lab, looking around attentively and smiling broadly, apparently pleased with the large, well-equipped space. Witherspoon hadn’t been entirely sure what he might enjoy tinkering with, so his lab was stocked with tools and supplies for every eventuality, from large vats and ovens to a watchmaker’s desk. Fritz had placed the case on a lab bench and taken out a beautifully crafted device that looked like a miniature carousel. It had turned out to be a music box, but rather than the typical key for winding a mainspring, one simply poured hot water into this one through a delicate funnel. Witherspoon had been delighted with the device — not least because it played a variety of well-known tunes, one per ounce of hot water, and no matter how many times he activated it, he couldn’t fathom what became of the water. It didn’t pour out the bottom of the carousel, and he was sure there wasn’t room inside the thing for a tank large enough to hold as much water as he’d poured in. Fritz would only say “water used up”, and beg off further explanation due to difficulties with the language. Witherspoon had hired them on the spot. One of his objectives, at the time, had been to discover just how the carousel worked, but in the five years Fritz and Imelda had worked at the lab, the carousel had been on display in the library and even used from time to time, but the doctor still had not persuaded his assistants to explain it to him.’

In truth Fritz and Imelda were much more than the typical laboratory assistants. Because Witherspoon’s talents ran more along the lines of business and finance, they essentially ran the lab almost entirely. The doctor had stocked an extensive library to Imelda’s quite eclectic specifications and added tools and raw materials whenever Fritz asked for them, but aside from launching one project or another by saying something like “wouldn’t it be interesting if a steam engine could power a laundering device for one’s home”, the putative doctor puttered away at his own projects and mostly stayed out of the way of his assistants. And even his own projects, more and more, involved the various adding and calculating machines he collected. Not modifying or improving them — simply using them to manage his finances, which continued to grow in both value and complexity.

For their part, Fritz and Imelda settled into the Doctor Witherspoon Laboratory (as the ornate sign over the front door would have it) quite comfortably, and provided the doctor with a steady stream of inventions to describe and demonstrate at the Inventors Club. Some of them even resulted in revenue — which Witherspoon, to his credit, assigned nearly entirely to an account he had established and transferred to his assistants. By now, of course, Fritz and Imelda had accumulated enough to live comfortably on their own and even potentially establish their own laboratory. But in the closely proscribed social circles of Byronton, particularly in the area of inventing, which the city-state considered its watchword, heritage, and biggest source of pride (not to mention wealth), the pair would never be able to open a sanctioned laboratory with its own official proclamation of something framed near the door, and more importantly, would never be admitted to the Inventors Club.

Thanks to the Byronton government’s nearly incomprehensible complexity and bureaucracy, not to mention a corpus of legal statutes stretching back nearly three thousand years and thriving community of attorneys, nobody was quite sure whether anyone foreign — that is to day, anyone who spoke with an accent — was legally entitled to any remuneration from an invention they introduced. There were precedents on both sides of the issue. Nearly a century ago, an inventor named Bergonhiff — who by all reports had spoken with a very pronounced accent indeed — had managed to profit from the method he had invented of processing coal so that it burned more evenly and completely. But people also still told the story of Ourelealinnea, who had not only retained his accent but was quite open about having been born in the Mervyinean Islands. Ourelealinnea had invented the type of rotary governor still used on many steam engines to ensure against excessively rapid cycling, and he had been denied all attempts to profit. At least in the stories, he had afterward left Byronton, either returning to his native islands or emigrating to Kratch, Byronton’s great national rival. Even so, Byrontonians thought a great deal of tradition, and all steam governor assemblies were still marked with a stylized “O” for Ourelealinnea even though they were manufactured by several different firms.

After Doctor Witherspoon completed his purchases at Filson and Nobbs Mercantile and gave instructions for their delivery, he proceeded to the remainder of his day’s business. He visited his tailor to place an order for a new waistcoat, was fitted for boots of a new design he had envisioned, incorporating pockets to hold various tools and implements in plain view, primarily as additional evidence of his inventorly eccentricities, and had tea at one of his other clubs, the Columnar Society. The Columnar Society was a club of businessmen and accountants, and Witherspoon greatly enjoyed the atmosphere and company he found there. They took little notice of his adopted eccentricities, understanding that inventing was simply his business, and one made allowances for the requirements of one’s business. Witherspoon relaxed at the Columnar Society to an extent he never felt able to at the Inventors Club, and he fell into an extended conversation about the likelihood that prices of this or that commodity would rise or fall as a result of current events. As it happened he found himself still at the Society when it was time for supper, so he stayed. After more conversation and imbibing of postprandial cocktails, it was quite late when the doctor returned to the laboratory.

Fritz and Imelda had long since retired, but had left a note for Witherspoon. It read only “must speak in morning”. Witherspoon blinked. Somehow his assistants managed not only to speak, but to write with an accent as well. He took the note with him to his chambers, wondering briefly what the morning would hold.