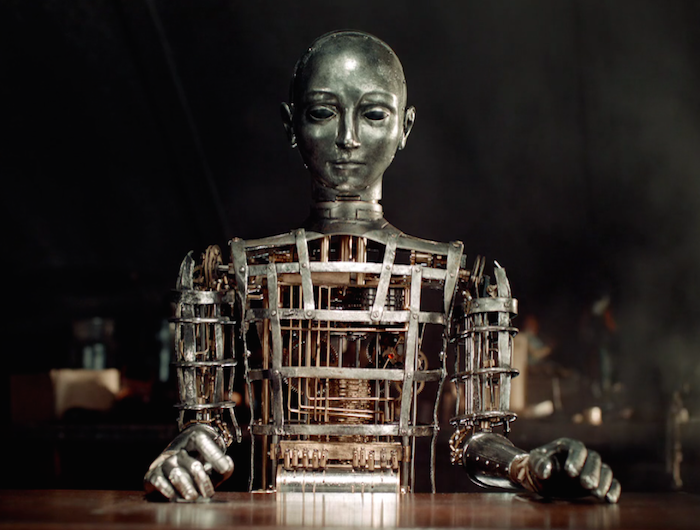

Ronald spent the next two days and nights in the laboratory, first disassembling the automaton’s components even further, looking for jammed gear trains, wobbles in tiny jeweled flywheels, checking intricate glass parts for cracks, and testing India rubber seals for leaks. Finding nothing, he began to reassemble Elektra. When the gleaming figure was complete, Ronald called the professor from his adjoining library. “Professor, I checked everything,” he said, “she…I mean it should be ready.”

“Excellent,” said the professor. His uncharacteristically jovial mood made Ronald suspect that something other than the disabled automaton had been occupying the professor’s time. Professor Q went through the complex steps required to restart the flow of ectonic energy throughout Elektra. Ronald wasn’t entirely sure what ‘ectonic energy’ was, but knew it had something to do with the odd liquids the professor poured into the machine’s three intake ports, and was also related to the strangely shaped crystalline assembly hidden deep inside the automaton. The professor had fashioned that device himself, without any assistance from Ronald — that alone was unusual enough to have raised Ronald’s curiosity, but despite having had several opportunities to study the odd crystals, he still had no inkling how the system worked, or even what exactly it did.

Ronald and the professor followed the detailed list the professor had recorded in a leather-bound notebook he normally kept locked in the laboratory safe. Not the large safe easily visible in the back corner of the lab — that one was, despite being as impregnable as possible, just a decoy, the professor had assured him. It was filled with items of real value, but the things the professor placed real value on — his notes, logs of experimental findings, and detailed designs — were kept in a vault hidden behind a false wall in the professor’s library.

They progressed to the final step; the oddly archaic process of inserting a cast iron handle into a keyhole in the automaton’s back, cranking it exactly five and two-thirds turns clockwise, then removing the handle and pressing a hidden button beside the keyhole. There was a click, a soft whirr as carefully balanced gears began spinning. A moment later Elektra’s eyes began to glow again.

“Elektra,” said the professor, “please perform an internal assessment. Are all your capabilities intact?”

The automaton took several moments to reply, during which Ronald recalled the self-assessment procedure he had painstakingly programmed by assembling a complex series of cams, sprints, belts, and hand-cut sprockets. As he always did, the professor had left out key details when he had explained the task to Ronald, but the process was clear enough in the end. Finally Elektra spoke again. “Capabilities are all in order, professor. Do you have another task for me?”

“No, Elektra, that will do for now. You may proceed to the library and peruse any volumes you wish,” said the professor. Ronald still wondered about this aspect of the automaton; the professor behaved as if Electra could actually read texts and understand them, even though internally Ronald knew the process was little more than a clever system of recording the texts by means of refracted light and a process of chemical etching on a stack of silver plates thinner than paper.

And yet the automaton did on occasion appear to do more than simply recite back the information it had stored. Ronald recalled the automaton appearing to make a connection between a monograph concerning, of all things, the phlogiston conjecture, and an alternative theory positing some sort of gaseous characteristic of air itself. Still, he couldn’t be sure the automaton hadn’t simply recorded a third publication that Ronald had not been familiar with and echoed that back.

Electra walked into the library, leaving Ronald to tidy up the workbenches. As he did, he began wondering about what had happened to the automaton when Doctor Witherspoon activated his pocketwatch-sized device in the Inventors Club. The automaton had entirely ceased to function, but contrary to Ronald’s — and presumably the professor’s — expectations, there had been no damage whatsoever to its internal mechanisms. Ronald had expected that the piercing sound, which had cracked several glass objects in the hall, had also broken some of the automaton’s glass components, or possibly disturbed the exquisitely balances in some of the tiny, impossibly intricate assemblies of brass, gold, and jeweled bearing surfaces. However, in spite of his close inspection, he had found all of those to be perfectly intact.

But if there had been no damage to any of the automaton’s complex mechanisms, the problem must have occurred in the mysterious crystalline component, buried deep in the upper torso of the machine, that provided the motive power. The professor had devised that system himself, and had been just as secretive as he always was with his most prized inventions. He hadn’t shared the details with Ronald, but as the chief assistant Ronald enjoyed nearly complete access to the resources of the laboratory. Only the designs and notes the professor kept secreted in his hidden safe were kept from him. But he did have access to the several preliminary versions of each of the automaton’s components. Ronald realized suddenly that most importantly, he had access to the automaton itself. As he carefully returned tools to their assigned drawers and slots, Ronald imagined how pleased the professor would be when he was presented with the solution to Witherspoon’s device. Perhaps there would be a salary increase. The professor might even begin to include him in the design and planning of future inventions. Like all laboratory assistants, Ronald’s greatest wish was to become an inventor in his own right, with his own laboratory and his own membership to the Inventors Club. In the privacy of his own room, he even practiced with the various eccentricities he would be expected to adopt as a recognized inventor. He favored an exotic haircut — perhaps asymmetric and extravagantly dyed — complemented by a collection of unusual neck cloths.

The professor interrupted his reverie by announcing “Ronald, I shall be going out for the evening. After you finish tidying up, your duties are finished for the day. Please lock the laboratory doors before retiring.”

“Of course, professor,” said Ronald. He locked the doors after the professor left, just to make sure he didn’t forget later. Then, having cleared the workbenches, he entered the library where the automaton was gazing at a book, turning a page precisely every 37.4 seconds. “Elektra,” he said, “please come into the laboratory.”

The automaton stood up wordlessly and followed Ronald back to one of the workbenches. Ronald grabbed some sheets of paper and a pen on the way, which he placed on the bench in front of Elektra. “Elektra,” he said, slightly nervously. He wasn’t entirely confident this would work. “Please explain the operation of your central locomotivational unit. You may use that pen and paper to diagram the system if that would be helpful.”

To Ronald’s relief, and slight surprise, the automaton picked up the pen and without hesitation began to draw while it spoke. “My locomotive power is provided by ectonic energy,” came the words in the machine’s strange voice. “Ectonic energy is radiational in nature and invisible to human senses, but is available in ample supply in any location. The combination of crystalline beryl and galena, when encased in a precisely spherical metallic shell composed of an alloy of forty-five percent gold and fifty-five percent quiderium…”

The automaton continued for three hours, pausing only when Ronald interrupted to ask questions like “what is quiderium” (a metallic ore discovered by the professor; the refined metal was very heavy, amber in color, and generally nonreactive) or “what specific shape must the beryllium actuator take” (a double hyperboloid with a nonconvex icosohedron at the locus).

Ronald had to fetch additional paper and replenish the ink in the pen several times. Finally the automaton stopped.

“Is that all?” asked Ronald.

“My locomotive unit has been fully described,” said Elektra, falling silent again.

“Er…thank you, Elektra,” replied Ronald. “You may, um. return to your study in the library.”

“Thank you Ronald,” said the automaton, and it walked away. Ronald took the large sheaf of papers — the automaton had included both diagrams and descriptions — and stared at them for a moment. Surely this would be enough to find the flaw that allowed a simple sound to disrupt the system. Once again visualizing the professor congratulating him for taking the initiative, Ronald turned off the lights in the laboratory, leaving only the single lamp in the library, where Elektra was flipping a page every 37.4 seconds, and returned to his room. He was too excited to sleep.

Doctor Witherspoon’s Laboratory

By the time Doctor Witherspoon got back to his laboratory his violent rage had subsided. He had instead resolved to both extract his revenge on his rival, Professor Q, and regain access to the Inventors Club. Witherspoon did, of course, affect a number of the personal eccentricities that befitted a recognized inventor, but he was, at heart, a practical man who calmly assessed his options and carefully selected the course of action promising the main chance. That was, at the least, what he told himself.

He let himself into the nondescript gray stone building where he maintained his laboratory, and was met at the door by his two assistants, Imelda and Franz. The wizened couple, husband and wife, had worked with Witherspoon for many years. They were virtually interchangeable in the many duties they performed in the lab. Witherspoon would often begin a task with the assistance of one of the pair, and realize later that the other had stepped in so smoothly and seamlessly that he hadn’t even noticed.

“Good evening, Doctor,” said Imelda, holding out a cup of steaming tea. “The meeting, it did not go well, I think?”

“Is my mood so transparent?” sighed Witherspoon, taking a sip of the tea. “But yes, you are quite correct in your assessment. I’m afraid the evening was far less than satisfactory. The one glimmer of success in the entire sorry affair was the Self-Tuning Resonator. I had occasion to make use of it, and it performed admirably. But come, let us retire to the sitting room and I shall recount the tale in its entirety.”

Imelda and Franz listened quietly as Witherspoon recounted the events of his evening at the Inventors Club. After he was finished, Franz had only one question. “The professor’s automatic person…it is real?”

“I must regretfully conclude that it is not, as we had conjectured, simply an elaborate costume,” replied Witherspoon. “The device was disassembled into component parts, and in my judgement none retained sufficient size to conceal an operator, even a diminutive one. I still would not put it past that scoundrel to perpetrate an elaborate fraud…but I cannot see how it would have been managed.”

“I never shared your scorn at the stories of the robot,” Imelda said to Franz. “It conceals many secrets worth learning. But Doctor,” she continued, turning to Witherspoon, “you say the pieces of the machine continued to function after deconstruction?”

“Indeed,” said the doctor. “The machine in fact disassembled itself, you see. And when given a verbal command to move one foot, it complied, although there was no physical connection between the units at that juncture.”

“That is fascinating,” murmured Imelda, seemingly to herself. Then, rising from her seat, she said more loudly, “Doctor, Franz and I shall now retire to our rooms if you do not require our services?”

“Yes, yes, of course,” replied the doctor, “I believe I shall retire as well. We must consider our next courses of action. I have no intention of letting my expulsion stand, and I shall have my revenge on Q for the insult he delivered in such a public forum.”

Imelda mused that if the doctor had listened to her when she warned him against attempting such a public denunciation of an unknown invention, the entire situation would never have arisen. But all she said was “How should we plan to begin the morning, Doctor?”

“Ah, yes, excellent inquiry,” said Witherspoon. “As I see it we must pursue two paths in parallel. We must create a new invention of such surpassing impressiveness that I am welcomed back into the folds of my club. And we must prepare a way to provide the professor with the comeuppance he now so richly deserves.”

“I see,” said Imelda. “Perhaps, Doctor, we should begin a program of research into the two puzzles presented by the robot. How do its pieces commune without touching? And upon what principle is it motivated? You say you heard no sound from the machine that put you in mind of a clockwork, nor of a steam device?”

“Er, no, nothing like that,” said Witherspoon, “I was quite close to the thing and its operations were entirely without audible clues of those sorts.”

“Then with your permission,” said Imelda, “upon arising with the sun, perhaps I will meditate upon the ability of the robot pieces to commune, and perhaps Franz would consent to muse upon the question of locomotion.”

“Ah, yes my dear,” nodded Franz, “that would be a fruitful course of action. With your permission, of course, Doctor,” he added.

“Hum, yes, of course,” nodded the doctor. “Please proceed according to those notions. I have business to transact throughout the city tomorrow, so I shall be unable to join you.”

“Thank you, sir,” said Imelda, “we shall follow your thoughtful advice, as always.” With that, Imelda and Franz took one another’s arm and left the sitting room.

Doctor Witherspoon arose from his seat and glanced in one of the several mirrors placed around the room. He smoothed his elaborate mustachios, adjusted his monocle, and spent a few moments practicing the expression of steely resolve he planned to use in his appointments the next day. Satisfied, he exited the sitting room and proceeded to his personal chambers. There were, of course, even more mirrors there.