If you visit the Rose Center for Earth and Space in New York City, home of the Hayden Planetarium, you might also be interested in the exhibit called The Cosmic Pathway. It’s a very long (360 feet) spiral with signs and points of interest that represent the entire history of the universe, which is about thirteen billion years old. you can walk along the exhibit and see the points in time when things like hydrogen atoms, or stars, or planets first existed. At the very end, there’s a little box with a human hair inside. The width of the hair represents the length of time we humans have existed in the whole span of the universe.

It’s not much; the width of a hair compared to 360 feet. The amount of time people have been around, compared to the time the universe itself has existed, is hardly anything. And yet there’s something new in that tiny little time span the width of a hair. Up until very recently, we humans have had to wing it. Take a guess at how our actions would turn out, and hope for the best. But then on February 24 in 1954 something changed because a particular person was born. He wasn’t the only one to offer a fascinating alternative to just taking a guess about what to do, but he’s been an important one. His name is Sid Meier, and you might recognize his name if you’ve played any computer games that simulate reality.

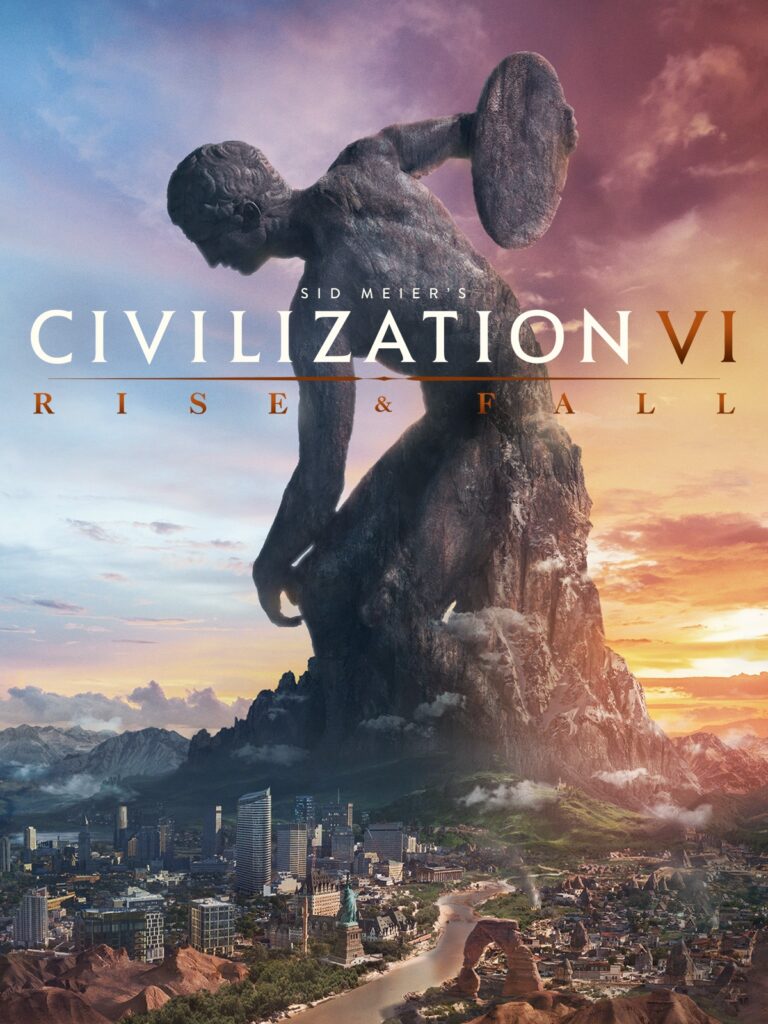

Meier was the lead designer on several kinds of simulation games, including Civilization, in which the player is put in somewhat accurate historical situations in humanity’s past and must make decisions about technology and culture to guide the development of a civilization. There have been multiple iterations of the Civilization simulation, and although the more recent versions are more complex and variable than the early editions, they’re still games. The situation is simplified, the decisions the player makes are limited, and most significantly, the decisions made by the competing civilizations are unsophisticated and governed by algorithms.

Nevertheless, the idea that you could test out your decisions in a contained environment and learn from the results — and that this could be not just a tutorial exercise but entertaining — I think this might be a fundamental advance in human development. The rule of thumb for human endeavors has always been that in the end you make your decisions and then you take your chances about what happens. But what if you had a chance to try it out first, without real-life consequences? What if you had a simulation, whether a game or something else, that let you try this decision or that strategy, just to find out what would happen? I think that’s a pretty good example of a learning environment. What kinds of fruitless, wasteful, deadly encounters might we avoid through a system like that?

On Februrary 23, 1949, the Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, formally ending the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. The conflict had proceeded in fits and starts for more than a year, with thousands of soldiers and civilians killed on both sides and not a great deal of change in borders or territory. Imagine what could have been avoided through an actually realistic simulation of the situation.

Or consider February 23 in 1983. That’s the day that a commission of the US Congress finally condemned the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. What if the people back in the 1940s had had a way to test their assumptions about Americans of Japanese heritage and learn before acting on their fears?

That might be the chief advantage of powerful simulations for supporting decision making; the examination and validation — or repudiation — of fear. So many human decision are made on the basis of fear. And so many of those turn out to be bad decisions. What if simulations — games like the ones designed by Sid Meier — evolved into realistic decision making tools that informed real-life choices? It’s not that outlandish; just imagine that before you hit the accelerator to race that other V-8 powered pony car down to the next light that you could glance at an app on your phone and see something like “chances of apprehension: 84%. Chances of accidental death: 67%. Chances of winning race: 12%.” If you’d already become accustomed to simulating your big decisions before actually taking the plunge, you might choose more wisely. And what is the point of all this human progress if not to give us a bit of wisdom here and there?