Imagine that you managed to qualify for and enroll in a top university despite all sorts of obstacles having been put in your way. You attend your first class, in a specialty you’re very talented in: math. And there, in your first class, on your first day, your professor asks you if you wouldn’t be better off just staying home.

That’s exactly what happened to Frances Elizabeth Snyder, who was born March 7, 1917, and went on to become one of the first six people in history (all women) to program the world’s first electronic computer, ENIAC.

If you’ve ever inserted a breakpoint in a program in order to better troubleshoot it, you can thank Snyder; she invented the technique.

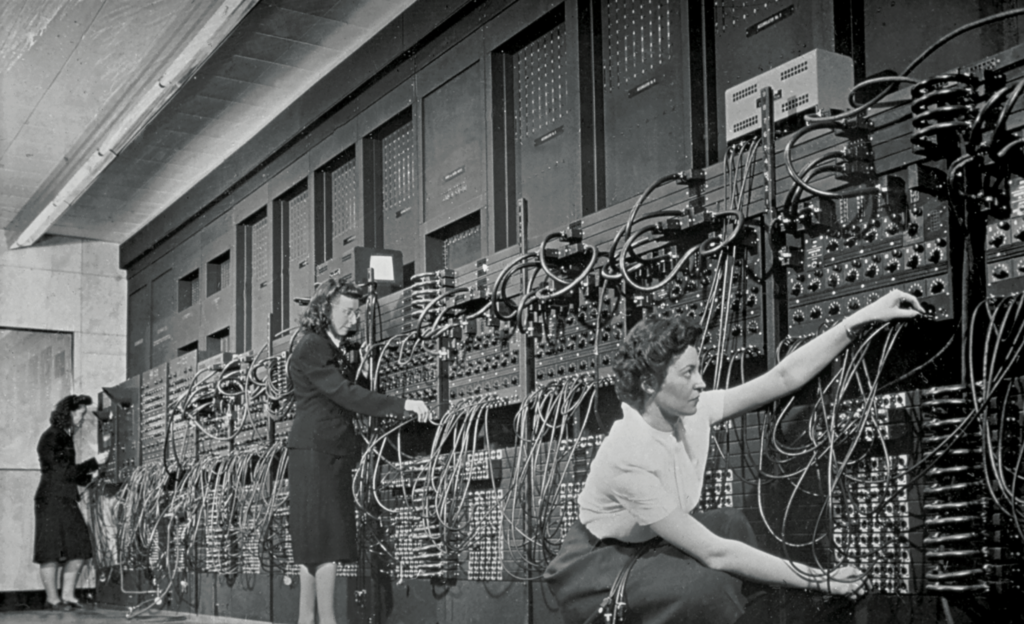

On that first day of class at the University of Pennsylvania, Snyder was actually majoring in journalism, not math. That wasn’t exactly by choice; it was 1940 and journalism was a career open to women at the time. Most other things weren’t. Nevertheless, she concentrated more on math, and when World War II began, got a job at the Moore School of Engineering to work on ENIAC. It was a highly competitive process; only six people were chosen out of hundreds. They were all women, partly because at the time “programming” wasn’t considered very important. In fact it was the women themselves who were called “computers,” not the machine.

ENIAC was classified, and initially Snyder and her colleagues had to program it without ever seeing or using it — they were only allowed to see blueprints and wiring diagrams. Imagine setting up a router with only that for information. They eventually got access to ENIAC, and after the war ended Snyder became Chief of the Programming Research Branch of the Applied Mathematics Lab at a Naval facility. While there she helped develop one of the next computers, UNIVAC, and you know how, on modern keyboards, the numeric keypad is right next to the alphabetic keys? That was Snyder’s idea too.

She helped write the SORT/MERGE routine that was the basis of mainframe computers’ sorting algorithms, wrote the management system enabling the computer to use ten tape drives for storage when one wasn’t sufficient, and wrote the world’s first statistical analysis package. It was used during the US Census in 1950. At the Navy’s Applied Math Lab she helped develop the instruction set for another early computer, BINAC, and worked with Grace Hopper to create the COBOL and FORTRAN languages.

She married John Holberton, and it was under her married name that she won the Augusta Ada Lovelace Award from the Association of Women in Computing, the IEEE Computer Pioneer Award, was inducted into the Women in Technology International Hall of Fame, and was the namesake for the Holberton School, a software engineering academy in San Francisco. She passed away in 2001 at 84 from complications from a stroke. You can find out more about her career in the documentary Top Secret Rosies: The Female “Computers” of WWII. It turned out that no, she wouldn’t have been better off just staying home.