November, 2022

It feels like there’s less hope in the world lately. Politics is nastier than it’s been in decades. European wars are back, and in the rest of the world many of them never left. We’ve changed the climate in ways we won’t even know about for years. People with fewer resources are finding it harder to get by. More people here in the supposedly wealthiest country in the world have no homes, not enough food, and of course we’ve managed to put together the worst health care system in the world. Opinions that are moderate are regularly denounced as “radical,” and “radical” is assumed to be unthinkably bad. Millions of people in the US seem to believe things they’re told without any evidence, even though there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary easily available. In a two-party political system, one of them seems to have decided the system itself — voting — doesn’t work any more.

So is there any hope for the future? Is there a future any more?

Well of course there’s a future. As for hope, I was going to paste in some sort of uplifting quotation, but wouldn’t you know it, quotations about “hope” tend to be so treacly they make my teeth hurt. They’re all about the abstract, idealized notion of hope, and if you’re going to use any of the dratted things you have to pretty much incline your chin and gaze meaningfully into the sky. Adopt a breathy, portentous voice for best effect, I think. I hate that stuff. We need to keep our distance from too much abstraction.

What I do think is that what might be happening is we’re getting a bit disconnected from our own language, and we’re definitely disconnected from our collective past. Taking things in the US first, we’ve been in this situation before. There have always been authoritarians around here distrusting democracy and voting and the whole idea that virtually anybody can have a say — at the level of a vote, a very small say, but a say nevertheless — in how the place gets run. Back in the beginning, two and a half centuries ago, the authoritarians carried enough weight that to get a vote you had to be white, male and own land. That prejudice is still with us, even though we’re not the agrarian society we were back then. Why else do you think a rural resident of, say, Wyoming is far better represented in our government than an urban resident of New York? Both states get two senators, but the ones in Wyoming and similar rural states represent vastly fewer people. That means a resident of Wyoming has a vastly better chance of making contact with one or both of their senators, and convincing them of something.

Except…that’s just the abstract version of how that works. In practice, if you want to get the attention of a senator, it doesn’t matter all that much whether you’re from a city or a farm. What matters is that you put in some effort. In the real world, being from a city might actually help you garner some attention, simply because there’s more potential attention right around you. If you want to get a message to a lot of people, you probably have more chances in a city than if your nearest neighbor is miles away.

One of the founding principles of the US, if not European civilization in general (or maybe even “civilization” overall) is doing less work yourself. Getting somebody else or something else to do it. This tendency has not, in the long run, been without serious side effects. Some of them are obvious: slavery, conscription, and I think you can list all the downsides of industrialization here too. People are lazy, but still driven to accomplish things. (I contrast this with my dog, who is at least as lazy, as a human, but perfectly content accomplishing nothing more than finding the most comfortable chair in any given room.) I think it’s that “accomplishing things” part that often causes problems, because when the accomplishment feels so important that you’re willing to overlook things you ordinarily would not — the misery of others, the poisoning of the water supply, air you can barely breathe — you go ahead and do it anyway. You might even feel badly about the side effects. But you go ahead anyway.

But here’s the thing about those side effects; they get more important over time. Slavery brought enough discomfort to enough free people that eventually they put an end to it, or at least pretty nearly. Poisoned rivers and lakes got bad enough about fifty years ago that something began to be done about it, and now many of those rivers are once again safe.

And that’s the basis, I think, for non-treacly hope. People are multifaceted, and although they often — all the time, for that matter — do things that have unfortunate side effects, those effects eventually get noticed by enough other people — even sometimes including those originally responsible — that fixing them becomes the aim. And sure, everything has unintended consequences because in addition to being lazy we’re not half as smart as we claim to be, so there’s really no end to it. But things do eventually get better. Before, of course, getting worse all over again.

Besides, even though it may seem like we’re on the verge of a “things getting worse” cycle, an important thing to remember is that there’s more than one cycle. Far more than one. And every cycle has a different pace and rhythm. We’re always on the verge of things getting worse, just like we’re simultaneously on the verge of things getting better. And even though I’m not fond of overly abstract quotes, here’s a good one: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” By the way, that’s not from Abraham Lincoln, Barack Obama or Martin Luther King Jr., although they all used the line. It’s from Theodore Parker, a Unitarian minister born in 1810 in Lexington, Massachusetts. He was a prominent figure in the Transcendentalist movement that produced so many of those treacly, abstract quotations. Oh well.

Before I get accused of “both-sides-ism,” I should point out that I have some much more pragmatic suggestions about hope:

- You can ban a book or an idea in one small context, but it will pop up more noticeably and stronger somewhere else, and banning it probably increases its scope.

- Kids today are just as smart as they’ve ever been, and just as capable of fixing everything us older folks have broken as we were at fixing the broken stuff we inherited.

- Authoritarians and ultra-conservatives are historically always wrong and everything they try to do disappears.

- The mega-systems that feed us information are currently broken, or a lot of them are. But people are also working on fixing those problems.

- The mega-systems that we rely on for commerce and goods and services are also currently broken or breaking. But there are fixes in the works for those too.

- Pure abstract ideas like “capitalism” or “socialism” or “liberal” or “conservative” are silly oversimplifications we came up with because of our laziness; simplified abstract ideas are much easier to sling around for entertainment. But not one of them is real.

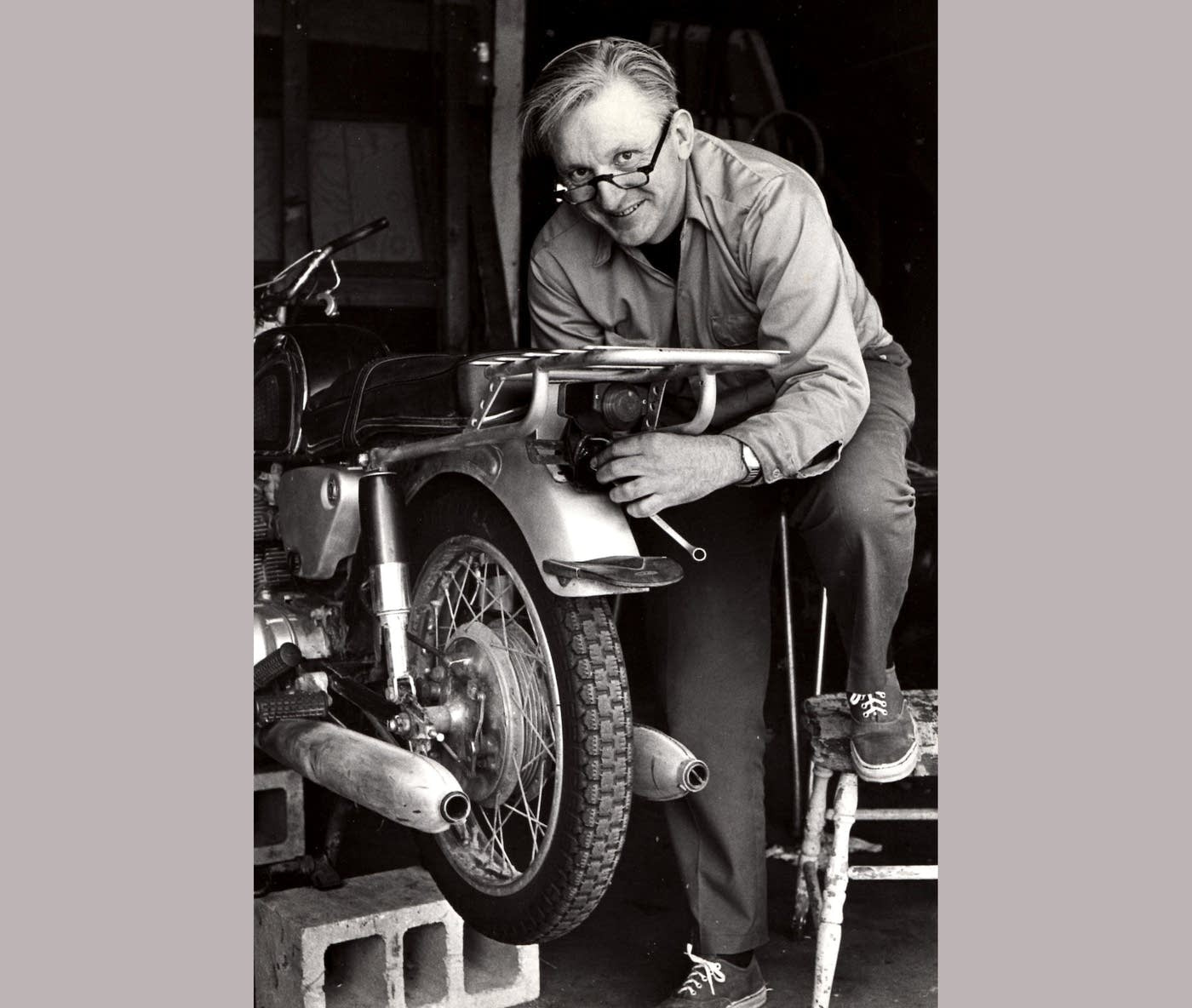

“And what is good, Phaedrus,

And what is not good—

Need we ask anyone to tell us these things?” -Robert Pirsig