The 1600s in Europe — specifically, in this case London, England — was a time when intellectually-oriented people started to correspond, meet, experiment, and publish. Scientists like Robert Boyle, writers like John Milton, philosophers like William Petty, and architects like Christopher Wren all knew each other and were in close touch. They created informal societies and organizations like the Hartlib Circle (begun by Samuel Hartlib) and the Invisible College, which was a sort of precursor to the Royal Society.

Right in the center of everything, and (probably) the host of the Invisible College meetings, was Katherine Jones, better known as Lady Ranelagh. She didn’t get as much credit as her brother, Robert Boyle, but the two worked closely together their whole lives. Boyle’s laboratory was in Lady Ranelagh’s London house, where he lived for over twenty years.

Katherine Boyle was born March 22, 1615, in Ireland to a wealthy and prestigious family; her father was the first Earl of Cork. It was a big family (15 children) and the Earl believed in education, so all of his sons were well educated. It’s not clear whether Katherine or her sisters were included in the tutoring, but if not, she managed to educate herself as well as her brothers.

The Earl of Cork wanted his daughters to live secure lives, and he arranged advantageous marriages for all of them. According to a custom that has since disappeared, Katherine moved in with another family when she was 9 because she was “assigned” to be married to one of the boys of that family. But the head of the family died, which dissolved all the marriage arrangements. When she was 15, Katherine instead married Arthur Jones, becoming Katherine Jones, and when her husband received his title (Viscount Ranelagh), she became Lady Ranelagh.

It was evidently not a happy marriage, and the couple mostly lived apart. This suited Lady Ranelagh quite well, and she pursued her own interests in her estate in Ireland and her house (aka mansion) in London. One of her interests was being a surrogate mother to her younger siblings, since their mother died the same year Katherine was married. One of her younger brothers was Robert Boyle, who shared her intellectual interests. If “Robert Boyle” sounds familiar, it should; he was virtually the first modern chemist (so was Lady Ranelagh, but he got the credit) and the author of Boyle’s Law relating pressure and volume. If we go by journal entries, it’s pretty clear that Boyle’s Law should at least be called the Boyle-Ranelagh Law, if not Lady Ranelagh’s Law. But in those days, women didn’t get the credit they deserved.

Lady Ranelagh was not only at the center of the intellectual life of 1600s London; she probably was the center. The Invisible College almost certainly met in her house (partly because it was the biggest), and she was an active member of the Tew Circle, the Hartlib Circle, and other intellectual salons of the day, many of which she hosted. In particular, the Hartlib Circle was a multinational group connected by mail, and all the letters were sent to Lady Ranelagh’s address.

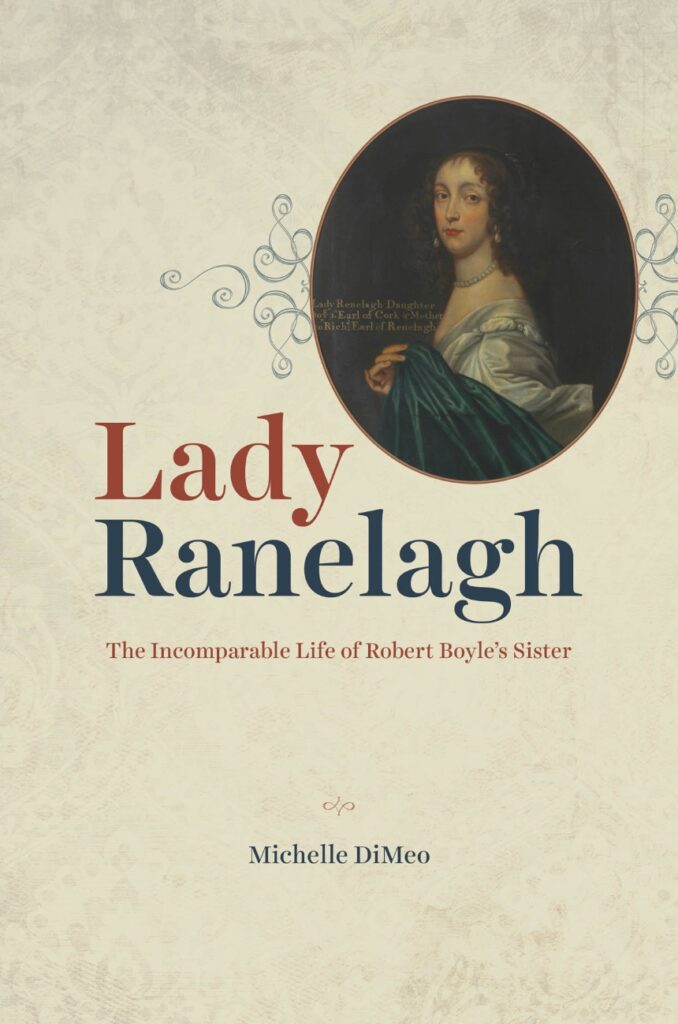

She was a scientist, medical researcher, and philosopher working in both political and religious arenas, and her incredible volume of correspondence shows that she was open to changing her opinion when new evidence arose. When she died at 76, one of her memorialists wrote “She lived the longest on the publickest Scene, she made the greatest Figure in all the Revolutions of these Kingdoms for above fifty Years, of any Woman of our Age” (that’s just the beginning; it goes on and on). Her biography, Lady Ranelagh: The Incomparable Life of Robert Boyles Sister, was published in 2021. There are biographies of Robert Boyle, too, but if there was any justice, at least one of them would be subtitled Lady Ranelagh’s Brother.