You know about the Brontë sisters, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne — all of them were talented novelists. But they had a brother, too, Patrick Branwell. He went by his middle name, Branwell, and while he was probably just as talented as his sisters, lived a short and troubled life.

Branwell Brontë was the only boy in the Brontë family. He was the fourth (of six), and was born June 26, 1817 in Yorkshire, England. Although four of his sisters were sent to boarding school, Branwell’s father tutored him at home, concentrating on a classical education. The elder Mr. Brontë apparently decided on home schooling when he remembered his own school experiences, which he described as “the strength of will of his own youth and his mode of employing it.” Sounds to me like he got into trouble in school and didn’t want his son to go through the same thing.

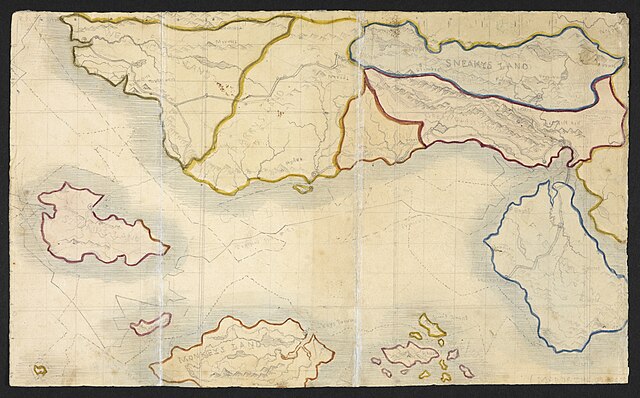

The two oldest Brontë sisters died before Branwell turned 8, and their passings affected him greatly. To distract himself from grief he threw himself into reading and fantasy role-playing games, particularly with his sister Charlotte. The two invented an elaborate imaginary world they called the Glass Town confederacy. It was set in western Africa, and they drew maps and wrote stories about it. Many of the stories still survive, and they even turned them into a novel, Glass Town, published in 1827 (when Branwell was only 10). The other Brontë sisters eventually participated as well, and each sibling had their own island, led by (in the case of the sisters) actual historical figures: Wellington, and the explorers John Ross and William Perry. Branwell’s island leader, on the other hand, was named “Sneaky.”

At 11, Branwell started producing Branwell’s Blackwood’s Magazine — a personal version of the real Blackwood’s Magazine, which he enjoyed for years. He even tried to get a job with the real Blackwood’s and wrote to them six times between 1835 and 1842. His letters were never answered.

When Branwell was about 12, his father hired John Bradley, a local painter, to give the Brontë children art lessons. The sisters were indifferent, but Branwell enjoyed art and showed real talent. When Bradley emigrated to the US a couple years later, Branwell continued to study art with another painter, William Robinson. When he was about 17 he did a portrait of his three sisters that now hands in the National Portrait Gallery in England. He originally included himself in the painting as well, but decided to paint it out.

When he turned 23, Branwell needed a job, and became a private tutor. By this time he’d started hanging out in pubs, and his letters to his “pub friends” detail some of his exploits — for one, he celebrated his new job with a “riotous drinking session.” His drinking may have affected his tutoring, because he was fired after just a few months. He tried doing translations of classic poetry and other works, and sent them to a couple of well-known writers who lived in the area. One of them, Hartley Coleridge, began an encouraging letter about the translations, but never finished it (the unfinished letter still exists).

Branwell’s next attempt at employment was as the “assistant clerk in charge” at a railway station. He evidently performed well, as he was promoted to “clerk in charge” the next year, 1841. But in 1842 he was fired because the sum of £11 went missing. Branwell probably didn’t take the money, but he’d gone off drinking and left a porter in charge, and the porter was the likely culprit. Branwell was fired anyway, but for “incompetence.”

He went back to tutoring, and got a job with the Robinson family, where his sister Anne had worked as a governess. That job lasted over two years before he was fired, this time probably because he had an affair with the children’s mother. For several months after he was fired, Mrs. Robinson sent him monthly payments, which historians believe was to make sure he didn’t blackmail her. Mr. Robinson passed away, and Branwell evidently hoped to marry Mrs. Robinson, but she turned him away, saying in a letter that he had “declined into chronic alcoholism, opiates, and debt.”

After that, Branwell’s behavior got more and more erratic, and he died at home, probably of a combination of tuberculosis, alcoholism, and addition to laudanum and opium. He was just 31. It’s unclear whether he knew about his sisters’ literary successes, although there is a story that his friends later said he had claimed to be the real author if Wuthering Heights, actually written by his sister Emily. He’s been portrayed in plays, novels, and at least four movies, from 1846 to 2022. In all of them, the main characters are his sisters. But in the 2023 novel My Brother’s Keeper, Branwell is at last a major character.

Portrait of the Brönte sisters by Branwell Brönte, when he was about 17. You can just see where he painted himself out of the picture.

Map of the Glasstown Federation from Branwell Brönte’s manuscript The History of the Young Men from their First Settlement to the Present Time, around 1831.