As an artifact of the 20th Century, the VW Beetle is many things — iconic, beloved, remembered, and weird. It started out as an idea sponsored by, of all people, Adolf Hitler (who is iconic and remembered but not beloved). It was a “car for the people”, which is even where the name “Volkswagen” comes from. and “the people” at the time were natives of Nazi Germany. Germany at the time — this was the 1930s — was impoverished on purpose; the countries that won World War I imposed sanctions on Germany for its part in that war. German people couldn’t afford cars, and for that matter couldn’t afford much. Hitler saw how the automobile was mobilizing Americans even in a global depression, and thought that would benefit Germans as well. So he sponsored a sort of competition for the design of an inexpensive, reliable car that could be built and used in Germany, thus stimulating the economy. The Beetle won. It was, for its entire (very long) existence, a cheap car. No frills. Things that other cars had didn’t arrive on VWs until later — things like gas gauges, turn signals, radiators (VW engines were air-cooled), and the like. The materials used to build VWs were nothing special, but somehow the design itself made the cars less susceptible to rust than many others.

The Beetle existed before World War II, and there were some variants made for the German war effort — most memorable was the “kubelwagen.” So as a German product, and a contributor to the war, you’d think Americans would, by default, hate and resent the things. Their ideas about VWs would include Hitler and the brutalities of the war. But that didn’t happen. Instead, VWs were imported to the US after WWII and became strangely successful, even in an era when efficiency was ignored and gasoline cost pennies per gallon.

Then when the 1960s came along and an anti-establishment counterculture gained steam, you’d think that VWs, being produced by the millions in industrial factories, would be at best ignored by the hippies and peaceniks. But that didn’t happen either; the counterculture embraced the things, reimagining them once again as mobile canvases for self-expression.

Then VWs, which were astonishingly underpowered even for their time, became popular for, of all things, a particular area of automotive performance as they were rebuilt into dune buggies so you could blast around the desert (or wherever) at high speed. Another idea overlayed on the odd little artifacts.

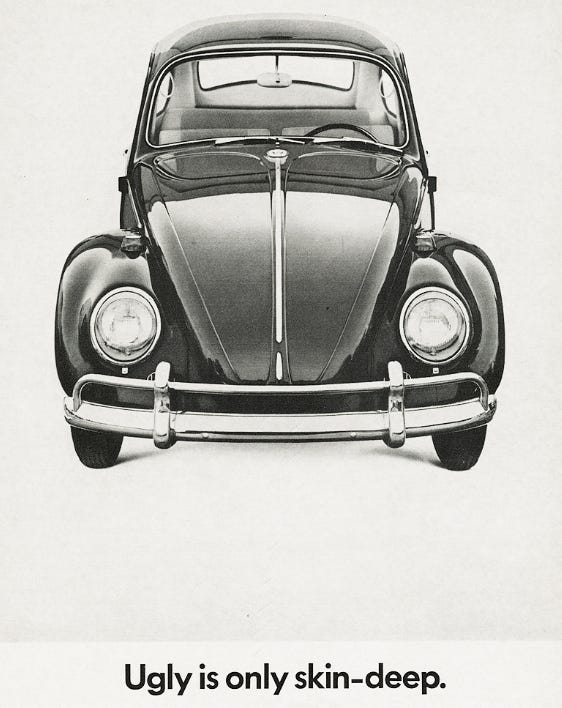

American advertising reimagined the Beetle in another way; in the days when advertising tended to be wordy, serious, and focus on detailed benefits, ads for VWs were quirky, funny, and terse. They were not beautiful cars, but that got reimagined as an advantage.

Maybe the lesson of Volkswagen Beetles is that people can think about anything in different ways. For one thing, they were paragons of high mileage back in the day, but really they only got between 20 and 30 miles per gallon (closer to 20). Nowadays that’s gas-hog territory. Sso far, at least, the things haven’t become images of inefficiency. But given their history, just wait.

History gets reimagined all the time. Chambers’ Book of Days was assembled in 1863 by Robert Chambers and published in 1864. In the preface, Chambers explains that the book was designed to consist of six categories, including “phaenomena connected with the Seasonal Changes,” “Notable Event, Biographies, an Anecdotes,” and “Articles of Popular Archaeology, of an entertaining character, tending to illustrate the progress of Civilization, Manners, Literature, and Ideas.” The sixth category is “Curious, Fugitive, and Inedited Pieces.”

Once you get to the information about any particular day, the categories aren’t quite as clear. But I think this would qualify as a Curious, Fugitive, or Inedited Piece:

“Two Lovers Killed by Lightning”

“It was on the 31st of July 1718, that the affecting incident occurred to which Pope, Gay, and Thomson severally adverted — the instantaneous killing of two rustic lovers by a lightning-stroke.”

Chambers goes on (and on, and on) about it in the wordy manner of late 19th Century prose. The young lovers were John Hewit and Sarah Drew, and they’d just received their parents’ permission to marry. The wedding was scheduled for the following week. Chambers goes on a bit about them, but I think the most interesting thing about the whole entry is that Chambers’ whole point is not that John and Sarah were electrocuted just before their wedding, but that three poems (by “Pope, Gay, and Thomson) were written about the incident. People back then were assumed to be more literate than we are today, so Chambers never identifies these poets beyond their surnames. I’m pretty sure, though, that “Pope” was Alexander Pope, “Thomson” was probably John Thomson, and “Gay” was most likely John Gay. Of the three, Alexander Pope (probably) wrote an actual epitaph to the couple. Thomson “appears to have had this incident in his view” when he wrote a poem years later in which a young woman (but not her beau) is killed by lightning.

As to whatever poem John Gay may have written about this, Chambers says not a word. Maybe we’re just supposed to imagine it. The interesting thing, though, is that what Chambers thought made the whole thing worth including in his book was that there was an incident, and then it got reimagined by three different writers. Or possibly, counting Chambers himself, four. And now, I suppose, five.