May 2022

It’s a funny thing about repetition — it’s great, but sometimes it can quite suddenly cross a threshold and become “too much.” The pulse of loud music is a good example; I can be enjoying it and then for some reason, I’ve had enough. I seldom see the threshold approaching. Maybe there isn’t anything approaching in the sense of a gradual buildup. Maybe it’s just a discontinuous event. Which, of course, is the exact opposite of repetition. Strange.

There are more and more electric cars around, and that means the sound of a powerful internal combustion engine might become a rare thing. It’s the sound of repetition; a drone of individual explosions so frequent it turns into one continuous sound, beloved by gearheads (or petrol heads, car geeks, etc) everywhere. If we do end up in a mostly-electric-vehicle world, I wonder if toddlers will still make “vroom vroom” noises playing with their hot wheels.

Repetition is so embedded in us, and our world, that it’s almost startling to find something that doesn’t repeat. The number pi, for example — an endless series of digits that don’t repeat. Pi has been puzzled over for centuries; and stories have been written about it. Calculate it out far enough and a mysterious message appears, written into the universe itself, but hidden from us until we get clever enough to find it. Real life has roared right past those stories, as it does. We’re up to 68 trillion digits by now and no secret messages. Not that anybody’s noticed so far, at least.

Did I mention that this issue is about repetition? I probably did, but what better place to repeat myself. I hope you like it.

Photography

I’m drawn to repeating forms when I’m looking for a subject to photograph. Simple tools and things made to be inexpensive but durable are good bets. Repeated simplicity is a powerful idea, and the visual expression of it can be a powerful image. Some color helps too, of course. This is a pile of commercial fishing gear — lobstering, I think — in Rockport, Massachusetts in 2017. Another iPhone image.

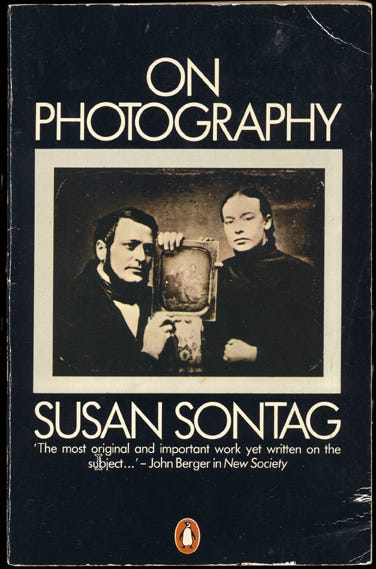

I often say I will never understand photography. Let me explain what I mean. It’s not the actual processes. I used to use a darkroom, and I have a basic grasp of how digital photography works. I even have a not-very-developed sense of composition, light, and color. What I don’t get is what photography actually is. Susan Sontag, in her collection On Photography, points out (as I understand it) that photography stands between us and experience. You can experience something, or you can photograph it, but not both. I feel something similar to that when I use a camera. It’s why I don’t like photographing people; there’s something about it that feels voyeuristic to me. I don’t mean there’s anything wrong with photographing people — if you can do it, more power to you. But it feels wrong for me.

I have, of course, photographed people. It feels okay to me when there’s an agreement between the subject and the photographer (me). A portrait, for example. That context makes it clear that the subject is projecting some kind of image they choose, and I’m recording it for them. Family photos feel okay as well; there’s a deep and complex network of understandings and agreements among families that can account for taking photos, even candid shots — which are the sort that can bother me the most.

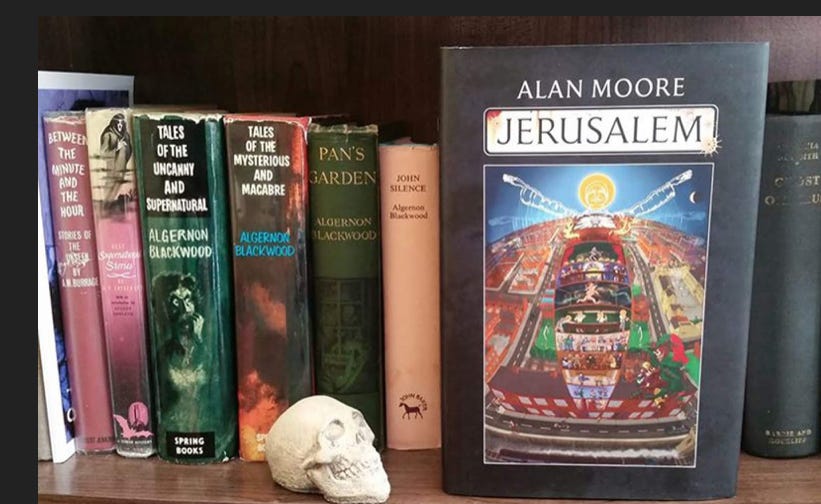

Another thing I don’t understand about photography is the relationship of a photograph — and this can be any photo, not necessarily of people — to time. Time is strange stuff that I think about a lot. Alan Moore has described a relationship with time as a solid, where you (or more precisely the angel in his novel Jerusalem) can perceive and access a moment of time simply as a kind of location, as if it’s fixed in a block of lucite. Your whole life is in there, fixed and unmoving; each instant is a place. Is that what photography is all about? Did anyone — could anyone — visualize time in that way before photography? Sontag held that the existence of photography has changed us, and how we think and perceive.

That’s what I’m still struggling to understand.