Lecturer Eamorie

Department of Antiquities

Byronton University

AP Box 2

Dear Professor,

I’m sorry to inform that I will be delayed in reaching the University; I was riding the evening train to Byronton when it unexpectedly lost its forward locomotion. We (that is to say the passengers) were informed (that is to say, by the conductor) that there was some problem with the motivating engine of the train and we were thus compelled to await an uncertain number of horse-drawn omnibus carriages to fetch us the rest of the way of our journey.

I met a traveling companion who has provided most interesting commentary and speculation about our immediate predicament. This fellow’s name is Ronald, and he is returning to Byronton after concluding some business, the details of which he quite properly refuses to disclose, for his employer. I find it particularly fascinating that Ronald’s employer, whose identity remains confidential, is highly placed in the fabled community of Byronton inventors.

Although rumors abound among all of us passengers regarding the potential reasons behind our stranding — the most popular having to do with a faulty or even corrupt practice having to do with the ordering and procurement of coal, which is of course essential to the proper functioning of the train. Its precise use escapes me, as it is not a subject of interest in Yamrick’s Principia, nor has it been dwelt upon in any of the classic texts with which I have developed great familiarity. However, my new companion Ronald offers an alternate speculation, one which he is at pains to point out is simply a flight of imagination. Nevertheless it strikes me that the idea is one I’ve encountered before as a faint echo in the most ancient of texts that have been handed down to us. Ronald’s idea is this: the train performs this same journey nightly, and whatever issues may have arisen in the orderly process of preparation, including loading the proper amount of coal, must have long ago been resolved. Therefore, Ronald proposes, perhaps there is a general weakening of the light and heat engendered by the process of combustion of the coal itself. Ronald assures me that this heat is associated with the chuffing sound produced by the locomotive, and is a necessary effect for the customary operation of the machine. If, says Ronald, the fire was insufficiently hot to maintain the necessary “steam,” an effect he states as being at the heart of the issue, then the operators would have been compelled to employ rather more coal than was customary. And that, rather than a lack of proper planning, could have proved the crux of the failure.

Outlandish as it is, and Ronald was at pains to assure me that it is a fiction born entirely from his own active imagination (I advised him to record the notion in a story he might have published as an entertainment), later I was musing about the Agenomicon. I believe that tome is among the most ancient text within our grasp, and it includes the legend of Pelomnion, the land that thrived then waned when the gods in their oasis in the Varin desert began to sport with the basic nature of that land — the water would no longer intermix with oil, the heaviest of weights became light as a feather while feathers themselves became so heavy the birds ceased to fly, and in particular, the fire was tamed so that a Pelomni could reach his hand into its midst without injury.

Perhaps Ronald has, by some coincidence, a passing familiarity with the Agenomicon, or at least the myth of Pelomnion, and thence sprang his fanciful idea. Nevertheless I am now fascinated by the reappearance of the myth in this manner. At the least it has served to pass the time we spend awaiting our rescuers.

As to my eventual arrival at the University, I am assured by the Conductor that the soon-to-arrive horse-drawn omnibus carriages (in reference, please see above) will transport us to the previously agreed-upon location. That is to say, the carriages are to take us to the Byronton railway depot.

From that interim destination I trust my previously established itinerary will prevail, though regrettably upon a schedule of necessity modified from previously agreed-upon strictures. While I believe I will manage to be in your presence tomorrow morning at 9 as we specified, I write this in the realization that no particular schedule has yet been communicated in regard to the time of arrival of the promised horse-drawn omnibus carriages, nor to the time (nor, to be honest, the day) of their final arrival.

Should this inconvenience you in any way, Lecturer Eamorie, please allow me the privilege of atoning for the problem at some point during my anticipated career as your student, as soon as it may happily commence.

Classically Yours,

Harry Pederman

————————

Dr. Professor Hammaradi

Byronton Investigative Institute

AP Box 4

My Dear Doctor Hammaradi:

I have interesting and potentially fruitful information to report following my investigation of the Lockean ruins near Destry. As you doubtless recall, after your approval of my course of study I resolved to attempt to trace the source of the legends surrounding the ruins. Growing up in Destry, I was of course familiar with the legends, but to me they had been simply stories — little more than Grissom’s Fables or the Cousin Stoat tales one recites for the amusement of children. I knew only that they were of ancient origin and involved the Lockean ruins.

Perhaps you are aware that the ruins have never been properly surveyed or explored. Children in Destry are strongly warned away from the area — the youngest with tales of haunting and evil. Older children are either told (as I was by my father) or conclude for themselves that these ghost stories are mere fabrications employed by parents to restrain their progeny from wandering into what they knew (or believed) to be a dangerous labyrinth of confusing passages, treacherous footing, and potential traps. By the time the Destry youth are old enough to perhaps behave responsibly toward such a place, the ruins have become for them nothing more than a vast rockpile, and more pressing matters of everyday life take the fore. Even the rare Destryman still harboring a glimmer of curiosity finds himself without the time or, eventually, the inclination to visit the ruins at all.

Accordingly, when I visited the Destry annals to discover whether any maps, accounts, or other information concerning the ruins might be found, there was very little to be had. There was a fellow in the previous century who schemed to excavate some portion of the ruins, believing he would find valuable artifacts, ores, and minerals therein. He managed to form a mining company and begin, but the venture was abandoned in six months’ time when nothing of value was ever found. No surveys were done, or if they were, they were not preserved.

Thus I equipped and provisioned myself with the limited stipend your department so kindly granted to the furtherance of my studies, and I set off alone to conduct my own survey. In the process I hoped to discover some hints as to the source of the Destry legends, in which the Lockean ruins are described as a thriving city of light, with wonders described in such detail that one is struck by the imaginative powers of the authors — or else their descriptive powers in recording what they in fact witnessed. My intention was to discover which of these alternatives was the case.

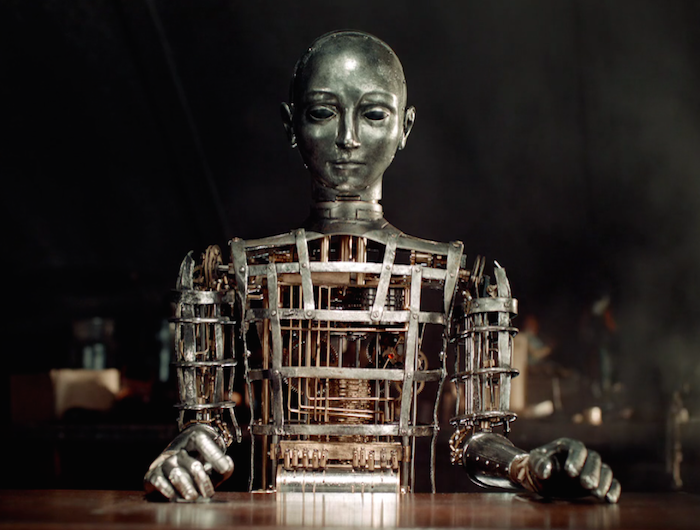

To me, the key to the intriguing nature of these legendary accounts has always been the absence of incidental emanations from the Lockean devices in the tales. The lamps produce the same illumination we enjoy today, but are said to produce no odor, smoke, nor soot. Conveyances described in the legends produce the same effective transport as do our trains and omnibus carriages, but they do so silently, and the locomotive impulse is said to have none of the side effects of combustion spewed by our machines. Indeed, the legends occasionally suggest that during the golden age of these ruins flame itself was unknown or at least considered entirely without use.

I cannot help but compare the Destrian legends to the somewhat more complete — yet similarly inexplicable — information and artifacts we possess in regard to the ancient Perenthian culture…

However, Doctor, here I must pause this missive. I am, you see, writing during an unexpected interval inserted in my return trip to Byronton by the failure of the train I was riding. The reason for the failure is unknown — the rumor amongst the passengers seems to be that the engine somehow ran out of coal, a possibility that seems absurd on the face of it. Nevertheless, omnibus carriages were summoned to fetch the passengers the remainder of the way, and I see they have arrived.

For the moment, then, I remain,

Your Student,

Michael Standish

————————

Professor Q

Q Laboratory

AP Box 1

Dear Professor Q,

I proceeded to Destry, which is the farthest point on the Byronton rail line, and conducted the experiments. My findings were approximately the same, saving that the temperatures I recorded in Destry were slightly lower than in the lab. I cannot say whether this is because the phenomenon is more advanced in the Destry area, or because there is a generally progressive deterioration in combustion and the time required by my travel led to the additional reduction.

I am writing this letter rather than reporting in person because I believe the cooling effect has affected the train itself; we are stalled many miles outside Byronton. I surreptitiously crept to the locomotive and discovered the coal bin to be completely empty. After a bit of calculation I believe the operators, being unaware of any change in combustion efficiency, attempted to maintain the train’s progress by using more coal, with the ultimate effect that they exhausted their supply. As the Automated Post (your invention, of course, sir) parallels the tracks and it seems clockwork mechanisms are not affected by the cooling of combustion, those of us among the passengers with the means and intention to communicate prepared letters such as this and inserted them in an AP box a short way along the tracks.

As we remain stranded until a series of horsedrawn conveyances can arrive to fetch us the rest of our journey to the city, conversation among my fellow passengers has introduced some interesting new acquaintances and some fascinating possibilities. I have had opportunity to discuss the situation — quite guardedly, of course — with a young scholar, Harry, on his way to Byronton University to study with Lecturer Eamorie. In the course of our talk I pretended to conjure up a flight of fancy that the failure of fire itself might be behind our predicament. Harry found it quite amusing, but a bit later mentioned that he had encountered something like this idea before, in an ancient book — possibly, he speculated, the most ancient book now known. It contains a story — generally counted as a myth, of course — of a land where this same effect occurred.

Even more fascinating is another passenger, Michael Standish, who works with Doctor Hammaradi of the Byronton Investigative Institute. He is returning after exploring something called the “Lockean Ruins,” and repeated some murmurings about ancient Lockean and Perenthian devices that operated on some principle completely divorced from combustion.

Is it possible, Professor, that this phenomenon we have tentatively identified might have occurred before, long, long ago?

I see the first of the omnibus carriages have begun to arrive, so I shall post this missive and attempt to return to the Laboratory at my earliest convenience.

Your Assistant,

Ronald