Originally published May 2023

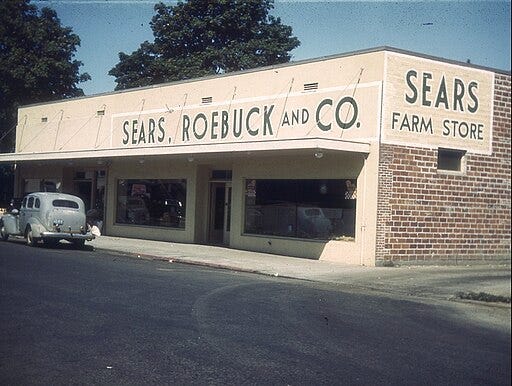

A couple of years back, Cory Doctorow coined a word, “enshittification,” that’s a perfect summation of why we can’t have nice things. Enshittification is the process that takes a service, or a system, or a tradition, or even an institution, and degrades it to the extent that it’s just no good any more. It applies to social media platforms, that start out fun and interesting and useful, and seem to end up — maybe always — like what Twitter and Facebook are nowadays. It also applies to anything else that can be turned into a “different kind” of value for a few greedheads, at the expense of something that used to be useful or reliable. Toys R Us, for example, or any number of other retail institutions, were purchased with “leverage,” which simply means somebody borrowed the money to buy them. Then the new owners had the business, but also owed all that money they’d borrowed in order to buy it. So they just assign the debt to the business itself — because now they own it — and before they pay the debt, they sell off everything they can and pocket thatmoney. Then they leave, and the business fails because it’s overloaded with debt it can’t pay.

But let’s focus, for now, on social media. Platforms have users, and to them a social platform can be a new kind of community. They can be ways to communicate with people you know, and then with other people who you’d probably never have the chance to meet otherwise. Maybe they share the same interest you have in collecting bottle caps, or talking about Star Trek, but they might live far away, or find it hard to get out much. Or maybe you find it hard to get out much. For the users of a social platform, it usually starts out to be all about friends and shared interests and connections.

Social platforms don’t just have users, though; they have founders too. By “founders,” I mean the people that probably had the idea in the first place, set up the servers and the software, and keep things running in the background. I think the founders of different platforms start with different motivations. Some probably start with the idea of creating a community of some sort. Some start with the idea of making lots of money. Maybe for most it’s a mixture.

Remember the enshittification of retail chains? Customers value the stores because they like the products, because they’re a convenient source of goods, and, who knows, maybe even because they enjoy visiting. Those are all valuable qualities, but other people see a different kind of value. A repository of cash flow, perhaps, or the land the stores happen to occupy, since a physical store has to BE somewhere. This group has figured out a way to take ownership of that other repository of value and turn it into cash they can take away. They leave what’s left of the business behind, and the original values it provided to customers? Gone. The whole thing got enshittified into a smelly puddle that just needs to be cleaned up. And not at the expense of the enshittifiers, either.

Whenever a social platform attracts enough users, by providing things they value, it acquires another kind of value almost as a side effect. There’s a repository of attention there. Attention is the kind of value enshittifiers like, because it can be turned into money pretty directly. All you have to do is flood the channel with ads, popups, sponsorship deals, and the like, and…ta da!…you’ve created a new stream of money you can pocket — if you own it. Cat Valente captured this process in the phrase “stop talking and start buying things.”

The repository of attention starts to waver, because it’s getting interfered with. So you just take down the guardrails that kept conversations on the platform friendly and civil and reasonable, because nothing generates attention like extremism. It might be a different sort of attention, but you don’t care. So the platform is even more enshittified, and fewer and fewer of the original users, and people like them, who just wanted a friendly place to chat, just leave.

Sometimes the original founders still own the platform, and they take this approach. That seems to be what happened to Facebook. Other times the platform gets sold and the new owners go this way. Twitter is the latest of these.

I think there’s a common thread tying just about every form of enshittification together: ownership. If you own a social platform, or buy one, you can enshittify it, and the evidence suggests that in nearly every case, you will. After all, there’s no substitute for money.

But what if nobody could buy it? A social platform is a little like an old-time village square that everybody could use together. The village square wasn’t owned by any single person or corporation; it was everybody’s. England had an arrangement like that long ago; there was land held in common that the common folk could use. That lasted until the elites (who quite resembled our modern enshittifiers) just flat took it. Enclosure, they called it; you can look it up. Pour a glass of wine first, because it will make you angry. Maybe the enclosure counts as a lesson learned; we’re supposed to learn from history, right?

In any case, let’s hope we’ve learned something, and let’s imagine that there could be a social site that assumes that the Internet is a public resource. It just needs a little more immediate and ongoing work than an acre of land might. It needs servers, electricity, a domain, programmers and designers, and some network admins to keep it all running well. That takes money, but this is not something completely out of our experience. We have lots of things that run on money but are public resources. Health care, transportation, defense, building codes — we’re actually pretty good at that sort of thing, and some other societies (“other” meaning outside the US) are even better at it. So all we need to do is create such a platform and keep it running, and we already know how to do that.

I’m not saying it would be easy — have you ever actually seen a website run by a public agency? But those are details to be solved. There are web platforms that people like to use, and there are public programs that work pretty well. So putting the two together must not be impossible. And that might give us at least one social platform immune (relatively) to enshittification.