I enjoyed Annie Hall when it debuted back in 1977. I liked The Purple Rose of Cairo, too, and Midnight in Paris. These are Woodie Allen movies. I don’t watch much TV these days, but back in the 80s when The Cosby Show was on, I remember enjoying watching it. For that matter, Pulp Fiction one of my favorite movies. Produced by Harvey Weinstein. I found Chinatown to be a great film too. Directed by Roman Polanski.

These people, Allen, Weinstein, Cosby, Polanski — they’ve all done some repugnant things. That shifts the background surrounding the things they’ve done (or at least been involved with) that I’ve really liked. When the context of something changes like that, and it has nothing to do with you, but maybe does have something to do with a work you connect with, it’s hard to know how to react. It’s like looking at color swatches to decide what color to paint your walls. In the light of the paint store, you like #74. But take them outside with the sun shining and #67 looks better. Clouds block the sun, and suddenly #67 doesn’t look so nice any more. But how about #77; didn’t consider that one before.

You might point out, quite rightly, that a movie or a television show is the result of the work of many, many people, and you can’t realistically judge it in the context of all of their behavior. So even if someone has a leading role in a film’s creation, should their bad— even criminal — behavior become a background so overwhelming that anything good about the final product becomes invisible?

And what about the other direction of this mechanism, if there even is such a mechanism? If someone who leads an exemplary life directs a dull or even reprehensible movie, should the context of their good behavior raise our opinion about the film itself? “His movie isn’t any good, but he was a really good guy so we watch it again and again anyway.” That doesn’t sound very plausible.

I can simplify the question, too. A movie is a group project, but what about a solo artist who has — or may have — behaved very badly? Carl Andre is a well-known sculptor whose work is featured in museums and gallery shows. He was married to the artist Ana Mendieta. In 1985 she died from a fall from their high-rise apartment unit. Andre was tried for murder. He was acquitted, but not everyone was convinced, and protests followed him to some of his shows. We can’t know for sure whether he was involved in Mendiata’s death, but is that even the real question here? What if we did know for sure that he was guilty? That wouldn’t change his sculptures at all. But it would change the background. We would see his sculptures lit by full sunlight, so to speak, instead of by an overcast sky. They would look different. Maybe.

I’ve looked at February 19 as a source of people and events that we can see differently depending on the background we’re aware of. In fact, sometimes the date itself forms the background. See if you feel one way or another about Aaron Burr when I explain that it was February 19, 1807 that he was arrested for treason in Alabama. If today happened to be March 4, I might introduce Aaron Burr as the third Vice President of the US, inaugurated that day in 1801. Or today was July 11, Aaron Burr might be introduced as the man who killed Alexander Hamilton on that day in 1804. Each of those is just a single factor in the background of a complex person. As what passes for the author here, I can emphasize whichever ones I want to, as any author can.

Authors are not the only ones to manipulate the context of people and events. It happens in various kinds of disputes all the time. Some of you may remember the name Karen Silkwood. Today is her birthday; she was born in 1946 in Texas, and worked at the nuclear fuel generation site in Oklahoma. She was a union activist and raised questions about the safety practices at the plant. She was carrying documentation to meet with a reporter when she died in a car accident. There was some evidence that the incident might not have been completely accidental. The whistleblower evidence she gathered turned out to be legitimate, forcing the company to update their safety practices, and finally close the plant and pay a settlement to her estate. But in the meantime, the company tried to change the background in other ways. They tested her body for drugs, and found that she had probably taken a sedative before the accident. They argued that when her body and clothing tested positive for high levels of plutonium contamination, she must have done it to herself on purpose. And so on. The thing about raising issues like these is that they alter the background, whether they’re later found to be true or not. And sometimes it doesn’t even matter whether they’re true.

Take the case of Ezra Pound, the poet. It was February 19, 1949 when he was awarded the very first Bollingen Prize in poetry by the Bollingen Foundation. It’s a prize awarded just once every two years for either the best poetry written in the US over the previous two years, or for lifetime achievement in poetry. It sounds like quite an achievement. But on the other hand, have you ever heard of the Bollingen Prize or the Bollingen Foundation until right now? It was created in 1945 when Paul Mellon, an heir to the Mellon family fortune (the same fortune behind Carnegie-Mellon University) gave a $10,000 grant to fund a small publishing house. It was named “Bollingen” after Bollingen Tower, a stone cottage built by psychologist Carl Jung in Switzerland. What’s the connection? The foundation was originally meant to publish editions of Jung’s works, because Paul Mellon’s wife Mary was very interested in Jung. So the prize for “the best poetry over two years” looks a little different when the background illuminates a foundation not even dedicated to poetry. Not only that, but that $10,000 from Mellon is all the money the foundation had, even though as a “Foundation,” you might think it was much bigger. And the prize? It was $1,000. Not nothing, particularly in the 1940s, but neither is it a particularly large sum.

And what about Ezra Pound himself? He was certainly a major poet whose work was respected and influential. On the other hand, he moved to Italy in 1924, approved of Mussolini’s fascist government, and supported Hitler. He went on the radio many times, attacked the US and England, and expressed pretty rabidly antisemitic views. When the Allies arrived in Italy, he was arrested for treason, but then they decided he was insane and put him in an asylum for over a decade. Pound’s background as a modernist poet got him the Bollingen Prize. His background as a fascist sympathizer and antisemite ignited enough controversy about the prize that the Library of Congress, which had been involved in the whole affair, washed their hands of the foundation and returned whatever money was left from the grant. The Bollingen Foundation lasted until 1968, when it was dissolved. But oddly enough the prize still exists. It’s now much better funded (by a new grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation) and it’s awarded by Yale University.

So the Bollingen Foundation is no more, Ezra Pound is not remembered very widely, and the prize originally created by Paul Mellon — who is also mostly forgotten — still exists, but now comes from a school originally disconnected from the whole affair. The background for these events has shifted like a kaleidoscope, even across a measly three paragraphs. And it can shift even more. Paul Mellon, you see, graduated from Yale University, and that’s why the school is involved now. As for Ezra Pound, well, Mellon was in the US Army during WWII, in Europe, became a major, and was awarded four battle stars. So he surely knew about Ezra Pound’s radio programs. And yet that initial prize was evidently OK with him. So what background did he see behind all those foreground details?

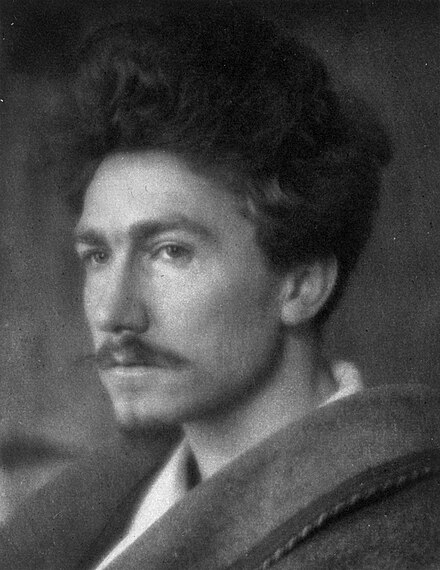

Ezra Pound, photographed by Alvin Coburn in 1913