April 2022

The title is a quote from the Cate Le Bon song Pompeii. It’s from the album of the same name. Le Bon’s music is spare, simple, and yet far more evocative than it at first appears. It can be pretty difficult, for me, at least, to figure out what some of her work is really about. Maybe what distinguishes artistic expression from prose is that you feel it more than think it through, at least at first. And then the feeling leads you to pathways of thought you never would have noticed.

Most of us get by pushing poets aside, but poetry is an art that may partake more immediately of feeling than does prose. This being spring, by the way, it’s a good time to read (or reread) Spring Rain by Robert Haas. It’s in his collection Human Wishes, where he ventured into the gray mist between, suppose, more lyric, “poetic” poetry and prose.

Cate Le Bon’s lyrics are not prosaic at all. In Moderation the chorus is:Picture the party where you’re standing on a modern age I was in trouble with a habit of years And I try to relate.

I don’t really understand what that means. But I understand how it feels.

This post is an attempt to go down some pathways of thought I never would have noticed otherwise.

Pompeii

Pompeii was a city near Naples, Italy. Not too far — indeed, not nearly far enough — from Mount Vesuvius, a volcano that erupted in the year 79 and buried the whole city under ten or more feet of ash and pumice. It happened over about two days, and most of the people who lived there — about 20,000 — escaped. But more than 1,000 died in the eruption. They hadn’t evacuated quickly enough, and when the pumice rain — unpleasant but survivable — was followed by pyroclastic flows the next day, it was too late. A pyroclastic flow is a very fast-moving, extremely hot cloud of ash, and it’s not survivable at all, not even if you’re inside a building. The city, and the last of its inhabitants, became fixed in time under the ash and stone.

Some of the survivors tried to return to salvage something of their lives, and there might have been some thieves and looters trying to grab anything of value too. The tops of some buildings could still be seen rising above the ash, and later some evidence was found of attempts to dig out here and there. But really the disaster was too big and too complete, and over the decades and centuries the city of Pompeii was forgotten. There were more volcanic eruptions, too, in 471 and in 512, that buried the place even deeper. And Pompeii faded from human memory and imagination.

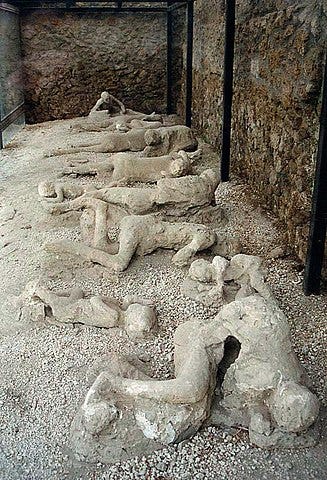

Until the late 1500s, when a project to dig an underground aqueduct to a mill in a nearby town (Torre Annunziata) accidentally discovered ancient walls decorated with pictures and texts. Nobody knew the name “Pompeii” in those days, and nobody really thought much about the discovery. A century later another excavation unearthed a wall inscribed with “Town councillor of Pompeii”, but it was misunderstood — they thought it referred to a villa belonging to a prominent Roman general named Pompey. Nearly another century passed before another inscription positively identified the place as Pompeii. Around the late 1700s, serious excavations began. Among other things, they discovered that many victims had been buried so quickly that their bodies were left in strange and sometimes gruesome poses. The bodies had decayed away, but left holes in the hardened ash. They injected plaster into the voids to recreate the forms of the victims, which were then put on display. Later — and even recently — clear resin is used instead of plaster, the better to preserve anything remaining, like bone fragments.

That’s the strangest thing, to me, about Pompeii and places like it. People died there, in terrible agony. Even those who escaped left behind their homes and belongings. Pompeii is a place of sadness and loss. But it’s also a tourist attraction, and has been for centuries.

We don’t go around digging up cemeteries to see what valuables people might have been buried with. Except that after enough time has passed, that’s exactly what we do. There must be some impossible-to-define point at which the lost change from our personal ancestors into “other people,” and then not even quite people at all.

What is that point? Nobody seems to have thought twice about extracting King Tut and his treasure from what was clearly his tomb. I think the idea must have made some people at least a little uncomfortable, but the only real expression of it turned into scary, superstitious stories and movies that represent preserved capsules of cognitive dissonance. There’s something not right here, we feel, but we can’t seem to express any rational objection.

But there’s pain in that stone we dig up.

Wheels

Places like Pompeii — sites of pain and loss, or of lost aspirations, or even of something we can’t know — are not rare. People leave things behind. Sometimes they’re the valuables they’re buried with in the hope that value, in another existence, will remain. Sometimes they’re all the minutiae of life, preserved by an event nobody foresaw. Sometimes we really have no idea at all what they are, but we sense they were made or gathered or crafted with immense effort and skill, and so must have been important, so we wonder.

But any of those things can be true of someone who lived a month ago, or a year, or ten years. We don’t generally excavate those, consider them ours now, and do more or less what we like with them. But there is that point when the people become others and the attitude we bring to the things they left behind (including their very bodies) becomes distanced and abstract, and we no longer care that we might be disturbing a grave.

I picture this, for some reason, as a vast wheel. There’s a set of books by Robert Jordan (and now an Amazon TV series) called The Wheel of Time. I was never able to get interested in the books, but I’ve always found that title to be both meaningful and powerful. If time is really a wheel (or, as in a quote from the HBO series True Detective, “a flat circle”), then that point when people — ancestors — become others not really like us might just be at the opposite side of the wheel from where we are. The wheel is turning, and it will come around again, and maybe that’s when we rediscover the lost city of Pompeii, or realize there are treasures to be found in those vast, mysterious, immensely ancient pyramids.

If you could stand aside from the wheel of time and somehow watch, maybe you could see when that change happens. When the people of another time and another place cross the veil of self and — possibly to their own surprise — find themselves in the mist of other.

What is it like to cross that veil? Is it perceptible? Maybe somewhere it’s an enigmatic cause for celebration; a glass is raised in a season of ash. We’ve been through a couple years of pandemic-inspired isolation, and otherness certainly seems to be on the rise. That veil may be around more corners than anyone expects. I wonder how we can learn to recognize it?